Via research we gather material for our case, our theme, our form and method of the planned research project, both in terms of the spread and the depth of our research. This phase comprises field work as well as (digital) visits in libraries, archives and geodata portals. At the beginning we search horizontally and seek to delineate the whole breadth of our theme (e.g. living together), the location (e.g. the street, the neighbourhood), the local, concrete context (e.g. the community, village, settlement, area) as well as the thematic contour (e.g. the single family house, the housing estate, squatting, materialities). We are therefore initially concerned with viewing as much material as possible, deciding whether and how it could be important for our case. The research takes place on a number of different scales and results – at best – in a collection of different formats, such as books, journal articles, photos, maps, drawings, reports, tenancy contracts, land use or zoning plans.

To research means to begin an interested search. This involves urban and community archives, libraries, museums and search machines, but also visits in the area during which we write a field diary (Fischer 2008) and/or a notebook. Chats with people on location can be productive both in terms of refining the research interest and data collection.

research activities

Under scientific research, we understand a number of activities and practices: we can purposefully look for something and gather information, systematically develop themes, get to know the background and historical development, get a picture of a complex issue. It is advisable to articulate hypotheses or questions and name keywords even before the research phase commences. During the research we have to iteratively embed new information and insights into the building of theses and questions as well as to probe deeper into information already gathered. Furthermore, we should review theses and research questions again, if necessary revise them and then work with them.

During the research we work with keywords, whether we’re working with search engines or library catalogues. It is therefore important to ensure that the search words (or keywords) are neither too specific nor too broad. The term »single family house« would surely lead to a large number of entries, whose viewing would take very long and, due to the thematic breadth of the notion, wouldn’t take us very far. The library catalogue pages explain how several keywords can be entered into a search either in combination or by excluding specific words.

While we collect data and material, it is imperative to view and read what we find very closely. Sometimes, the abstract of a longer text can give us a clear insight over whether the text is really important or can be discarded for now. What matters is that the researching person takes justified decisions as to why something could be important. Research and zooming in on a focus are mutually dependent, so you should always realise and reflect on your own questions and interests that drive this research.

Research material

The research material needs to be sorted (thematically or according to the kind of material), if possible using keywords so that you are able to find it easily. Central notions and terms can also be helpful in order to sharpen your focus or extrapolate the respective specificity of a case.

Kinds of material

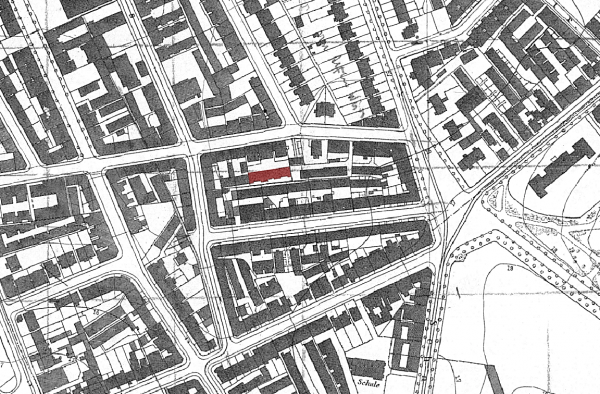

While searching for informative and revealing plans and maps, it is advisable to approach the research with concrete questions and then choose scales and kinds of maps accordingly. The scale of a map indicates the factor of its calculation into real measurements: at a scale of 1 to 1,000, one centimetre on the map equates to ten metres (1,000 centimetres) in reality. Furthermore it discloses the level of detail and the complete area that is mapped. A figure ground plan with a scale of 1:100,000 contains information that entirely differs from that contained in a technical drawing in a scale of 1:20. Yet both formats can result in interesting findings. For some residents, an aspect of the construction of their house may enable or disable specific ways of living, while for others, the urban location and surrounding typologies decisively shape their living.

In addition to the directly mediated data, maps and plans can be regarded as actants in their societal embeddedness, which is why they are not to confuse with objective representations of reality (Harley 1989). Every cartographic representation contains decisions about what is being represented and what isn’t, how different kinds of information are symbolically depicted and how they are hierarchically ordered.

Using documents, such as development plans from different years, it is possible to compare, for instance, politically driven and enforced urban developments with actual experiences in situ, and therefore to problematise such decisions. The respective official land values contain information regarding the prices that parcels of land (would) cost in the respective parts of the city. Official land valuation broaches current discourses about ‘prime location’ and ‘possible profits’. Using promotional material such as magazines for living and lifestyle, housing catalogues and property fairs can yield approximate indications about how living (in one’s own four walls) changes, what kinds of images of housing and living are produced and (supposed to be) shown and how all this generates and realises living knowledge (Nierhaus 2014) with a massive influence on the production of housing and living practices. Drawings of settlements, buildings and their floor plans show planning at a specific point in time in relation with a specific group of actors of clients and contractors. However, they do not or only rarely represent the built reality; at the same time, drawings hide specific rules and regulations of economic, ecological and social dimensions, such as funding guidelines for social housing (first and second order funding) that simultaneously express (often no longer contemporary or modern) social structures and hierarchies in the figuration of floor plans. Journal articles, descriptions and narrations give historical, contemporary as well as anticipated future impressions and insights regarding the respective case study – what are the narrations about a specific location, what kinds of discussions exist about a specific typology, how are social relations critiqued? Merging your own research to existing literature and theory, for example thematic fields such as the sociology of housing or architecture and urban sociology offers support in contextualising your own themes and narratives, weighing them and productively feeding them into the existing discourses. Research visits on site, even walks, can provide insights about who moves around in particular areas, what kinds of cars people have, what kinds of activities are undertaken on a daily basis. If you find old photographs relating to your case study, try taking a photo from the same perspective so as to sound out how and where the changes and transformations of the surroundings have materialised. You can search historical images and those in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons, apart from undertaking research in archives. Images and media in the public domain are those images and media (including texts) that do not have copyrights and are therefore open for all non-commercial purposes – if the sources are named. Images should be treated like texts as interpretable material that has been created from a particular perspective and with a particular intention.

Analyse the scientific sources and write a short summary for each source, noting why aspects, insights, arguments, facts etc. from a book or an article could be or are important for your research. Go through the reference lists in books and articles as they can give you clues as to who has when written about which themes and questions. Then, gather further and explanatory literature for each collected media type (material type) as well as to your analysis (photograph, film, documents, drawings, maps/ plans, texts, articles, objects) (cf. Flick 2009; 2016). If you repeatedly run across the same authors in different reference lists, this can well mean that their work is viewed as seminal. If these works also discuss findings or arguments that are central to your own research, you should find and review the original source, i.e. search this author’s work rather than reading about them.

A number of questions can help guide the analysis of images, maps, documents and texts, both in terms of the relevance of a source for your own research and in terms of the source’s statement and argument. Although these questions anticipate the analysis, they are also useful for the research, as they can help sharpen the focus, concretise the research question or even lead to a research question.

Questions for the critical photo (image) analysis:

Who or what does the photo show?

Which activities/ practices / relations can be discerned?

What role do perspective, section, surrounding, exposure, possibly colours, posture, look, gesture, (facial) expression of the photographed person(s) play?

What kind of impression does the image mediate/ is supposed to mediate?

(How) does the image affect me? What kinds of associations do I perceive?

Which information do I need in order to read and understand the image?

Who took the image and why?

What is not visible?

Questions for the critical text analysis:

What’s the subject?

Which theories/ methods/ matters of fact are discussed and how?

How can I describe style, expression, relation to other works and authors?

Which impression are readers supposed to get? Do you see an indication that a specific impression is sought to be mediated?

(How) does the text affect me?

What information do I need in order to understand the text?

Who wrote the text and why?

Questions for the critical plan analysis:

What is represented?

What parameters can you recognise? Which can’t you recognise?

What impression is the map/ plan (supposed to be) mediating?

How does the map affect me?

What information do I need in order to understand the map/ plan?

Who created the map and with what interest?

What is represented furthermore has to be queried itself: Do I try to find out something about the legal frameworks of development concerning the visualised areas? About the built-up neighbourhood and its historical development? About property relations and the parcelling of land? About proportions? About the quality of the land or technical infrastructure? Am I regarding an aerial view that shows details of buildings and greenery? Which scales show what?

Questions for the critical document analysis (Flick 2016):

Who/ which group of people have access to the documents when and how?

Who is the author/ are the authors of the present documents? Are they public/ official or personal/ private documents?

For whom and with which intention have these documents been created? Are these intentions to create, collect, publish etc. these documents personal or institutional?

What were the (social, political, legal planning) conditions during the creation of the documents?

What qualities do the documents have? What can they do? What functions do they have?

What kinds of representations (text, image, etc.) repeatedly feature?

Which representations are visible? Which representations are potentially missing?

As early as during the research it is paramount to be aware of the respective sources, and to be able to name them. If you don’t understand something or don’t know something, ask someone – in your class, the library personnel or via a search engine. Relevant aspects can emerge from so-called non-knowledge as soon as you recognise what you don’t know.

While you do the research, start an index of your material and indicate those sources that you discard over the course of your research. Use Chicago Style for your reference list:

https://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html

HCU Library catalogue

https://www.hcu-hamburg.de/it-und-medien/bibliothek/

University of Hamburg library catalogue

https://www.sub.uni-hamburg.de/startseite.html

Search for scientific articles online

https://scholar.google.com/

Search for plans and maps

https://www.hamburg.de/planportal/

HCU Geo data portal (connect via VPN)

http://gdi-hcu.local.hcuhh.de/

Search for images and media

Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page

Please always attend to copyrights and questions around licences before publishing your work!