Photography as a method is widely used in urban research, perhaps even more in architecture research, yet it is equally contested (Wyly 2010; Tormey 2013). Thanks to smartphones and digital photography, photographs are now even more mundane and omnipresent than at the time of analogue photography; they are media of communication, means for (self) presentation and documentation of the everyday. But until today, not many social scientists (sociologists, anthropologists) are using photography as scientific data.

Photos as data carriers

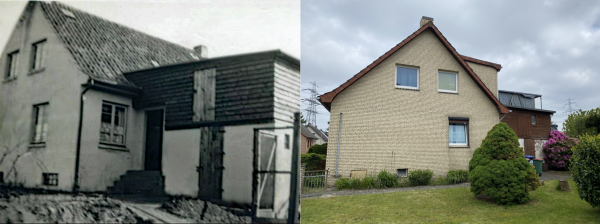

We all know the imaginary power of visuals from cities, squares, houses and people. Who doesn’t like to look at historical images that show the locations of our everyday in a former hue – or, conversely, show how little has changed compared to our current image of these locations. Using old photographs, places can be revisited; we can take new photos from the same perspective and capture the contrast between then and now, documenting how a place, a house, the passers-by, traffic, a facade or a tree has changed. Critical scholars use this approach to expose and address inequalities and asynchronicity in urban development (Marcuse 2009) or to start discussions (Wyly 2010). Especially this kind of ‘repeat photography’ (Doucet 2019; Rieger 1996; Harper 2013; Arreola & Burkhart 2010; Finn et al. 2009) can contribute to make visible and understand the agentic powers of urban change across long temporal distances. »Complex and interrelated forces of change, such as deindustrialisation of the urban core, the financialisation of urban space and real estate and the rise of gentrification take on a new level of clarity through photography that can enhance our theoretical and conceptual understanding of these trends.« (Doucet 2019, 412)

Photographing as a method

Taking photos in/of the city has been established as a visual method to understand complex processes of and within cities (Rose 2016; Béneker et al. 2010; Tormey 2013; Sidaway 2002; Banks 2001; Leddy-Owen 2014). Camillo Vergara (2016; 2014; 2013; 1999) documented with his photographic work US-American inner cities and presented the »new American ghetto«.

Boundaries of the visible

A number of aspects that later aren’t visible or retrievable in the resulting photos play an important role while taking photos. Of course we are confronted with the boundaries of the visible or demonstrable when we take pictures. Photography became a matter of heavy criticism (Sontag 1977; Barthes 1981). Roland Barthes stated that photography was violence because the accurately perceived representation of a person, a moment or a location negates any other memory of what is seen. Susan Sontag criticised the inherent prejudices and influences that are part of every photo, attacking in particular the phallocentric gaze that we reproduce unconsciously while doing photography. Both critics name the ambivalence: While photographs convey the assumptions of their absolute, impartial and universal truth, they are in reality only shadowy reflections of the past of one individual (Lemmons et al. 2014, 93). Yet instead of concentrating on the constraints, we can and should also see the possibilities of taking photos: photos should begin conversations, not end them (Wyly 2010, 504). In his programmatic paper Things pictures don’t tell us, Elvin Wyly (2010) carved out three central points that are of central importance for photography as research method yet aren’t mentioned by the images themselves.

Things pictures don’t tell us (Wyly 2010)

Firstly, there is the condition of their possibility, their coming into existence. We must consider and understand the context in which an image emerged as well as the conditions under which it was taken. These are the ‘invisible and therefore visually unknown contexts of the photographers and the material and social conditions that determined the decisions’ (Metcalfe 2015, 156) for a motif, a location, a section, an angle, a particular moment, etc. Wyly argues that taking photos can be understood like a promise or a debt towards those who are photographed and those who look at them. He therefore suggests that the conditions under which a photo is taken must be explained in order to keep a promise or pay the debt. This includes not only describing what happened while taking the photo but also what didn’t happen: »The task is to recognise that the photograph was torn from the context of infinite continua of time and space – and that we need to tell a story that describes at least part of that context with care, honesty and integrity.« (Wlyly 2010, 506)

Secondly we must note that a photo is taken out of its historic context, both in the moment that we take it and when we look at it. According to Susan Sontag (1077), the photo is a »neat slice of time, rather than a flow;« it says little to nothing about anything that happens outside of this specific time-space or what is (not) represented or captured. When we look at a photo we don’t know automatically what we see why and how (mediated), where the photographer stood, what the photo is supposed to say. In order to respond to these questions, we have to reflect on our own perception and pose critical questions: what is visible / invisible / not visible – not only on this photo but also at other times and other places? Does the photo show something that is well known or, conversely spectacular for this time and this place? From whose perspective, and are there differences?

Thirdly, the images tell us nothing about power and representation. Stereotypical images can be used to strengthen and legitimise existing inequalities and power relations. Similarly, photos can replicate social constructions easily, leading to »significant gaps and historical amnesia« over what is being represented.

Geographer Gillian Rose who employs a feminist position towards photography argues that »visual imagery is never innocent; it is always constructed through various practices, technologies and knowledges« (Rose 2012, 17).

Captions

Good, explanatory, descriptory and focusing captions can be extremely important for using photography in research. The caption provides the »things pictures can’t tell us« (Wyly 2010). They shouldn’t only relate time and place and what is presumably obvious in being pictured, but also bear in mind Wyly’s three points:

First, we have to carefully honestly and with integrity give back the context from which the images were ripped – e.g. through a caption. Secondly, we have to ask critical questions when looking at photos, questions about the conditions of production of the photos. Thirdly we must handle the content of the images critically and question whether they present or reproduce stereotypes or and whether we have unconsciously internalised them. If so, can we consciously break these internalisations?

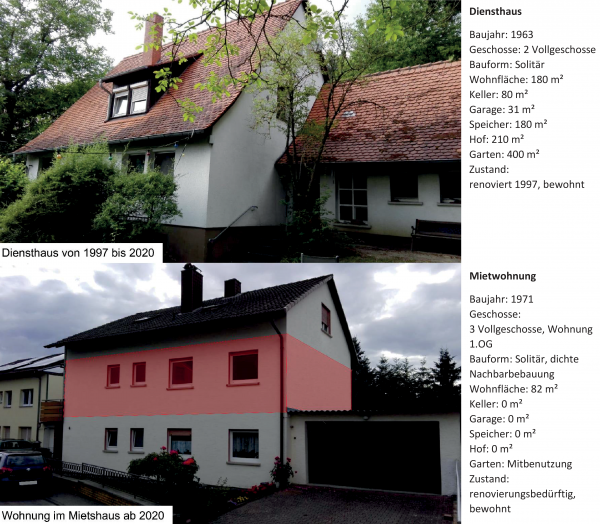

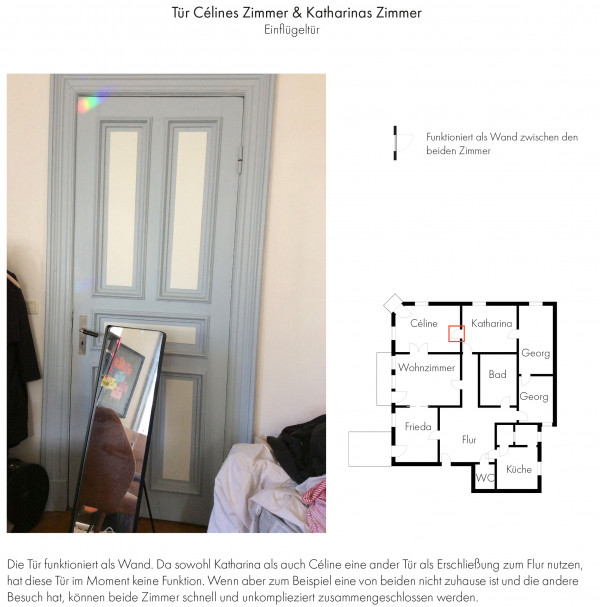

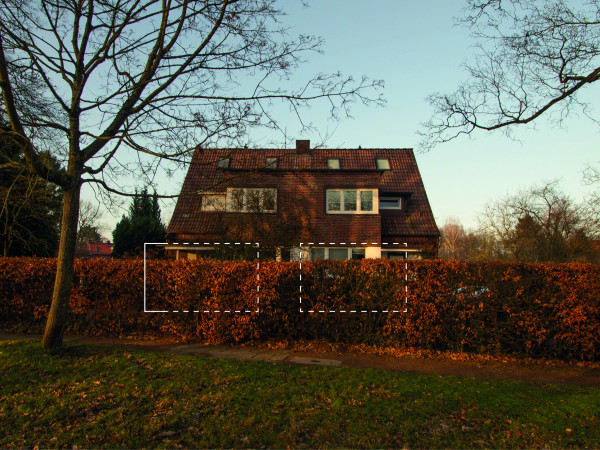

For the house and housing biographies photos are important formats both for data collection and for the representation of the findings. Ethical questions and the points raised by Wyly and others must be considered at all times. If a person would rather not see their face in an image used for research, but the physical presence of a person in the photo is important for the research, it is possible to draw over a photo in an attempt to anonymise the person or specific contents and aspects. This has been done very effectively in the photo series of the semi detached houses in the case »serially – individually« by Kurzweg / Treiber who have redrawn the transformations to the original house type. You can also use the method of repeat photography for house and housing biographies if inhabitants provide photos from past times and allow you to use them. You can then take a photo of the same motif from the same perspective and use this contrast to show transformations and tendencies (e.g. an increasingly tilting house or a neighbouring building that disappears or a new built house in the background, etc.) or, vice versa, to show continuities (a tree that outgrows the house over time or the carefully renovated windows of an old house).

In any case, every photo used in research requires a qualitative and qualifying caption that names what we see on the photo and tells the reader what deserves particular attention. The more context is given in a caption the better a photo can do justice to its task of representing and figuring as data.

2. Akt: Darsteller:innen und Requisiten