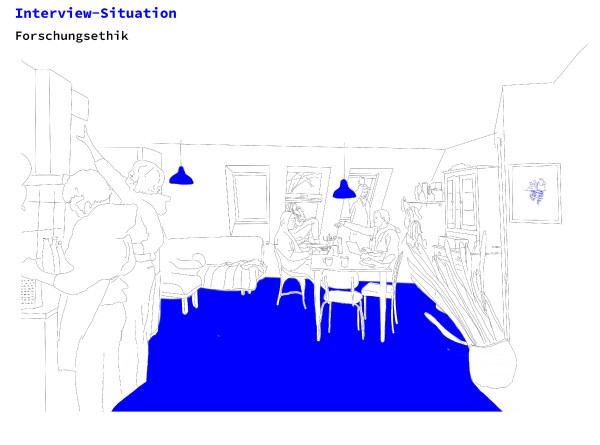

Observation is a central part of the ethnographic process in research. The observation or observing as method means to be part of the examined situation (participatory observation). Through taking part or at least by noting visually the interaction in a situation, it serves to record and understand the field. We distinguish between overt and covert observation: Do the participating and observed actors that I am observing and studying them? In the context of house and housing biographies we can principally only use the open, overt observation, as the inhabitants will have to invite the researcher (myself) into their house or flat and declare their consent for the research to be undertaken. Because the research interest is aimed at the living practice and the use of the flat / house, the researching person is always dependent on the participation of the inhabitants. The tour of the flat / house, observation, talk and interview are somewhat overlapping and complementary, although they can of course take place at different times.

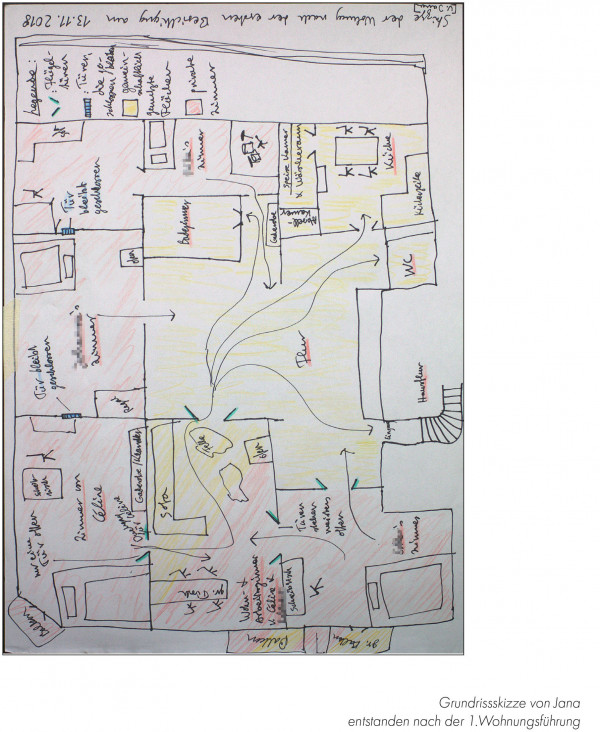

What is taking place can be observed and described both as a series of individual moments as well as in connection and in relation. The description of the observed (field notes and rich descriptions) can and possibly also should be enriched through photographs, drawings and material from the field (e.g. a flyer or letter, a rental contract or something that is described). During the observation is is important to reflect one’s own perspective, e.g. to keep asking oneself while observing in how far my own impressions, assumptions and expectations shape or influence the observed interactions and occurrences (cf. Pink 2013). It is therefore central to describe as detailed as possible, even what seemingly might not be important or only incidental, and to record what is taking place without evaluating it. The observation pursues the aim to retrace and comprehend interactions and / or situations, and doing so from within. If the observation is combined with other methods, such as the interview, one’s own perception of the observed can be complemented and / or contrasted with other perspectives (of the interviewee). The description of the observation can be subject to iterative loops of interpretation and consolidation. Sarah Pink (2013) for instance, distances herself from understanding observations (or, better: visual ethnography) as data collection and argues that visual ethnography is more a knowledge production than mere data collection: »I understand ethnography as a process of creating and representing knowledge or ways of knowing that are based on ethnographers’ own experiences and the ways these intersect with the persons, places and things encountered during that process.« (Pink 2013: 35) As the central objective of the house and housing biography is the knowledge production – the questions how people actually live in houses and flats, what living in houses / flats means for individual people, so as to generate conclusions for future living and the production of such future living arrangements – this extension is useful. We’re not concerned with collecting data and analysing these in the next step. The ways in which we observe, our assumed perspective and how the observation is brought to representation are already decisive steps in the knowledge production.

How to observe living in houses?

It may at first seem difficult to understand living in houses as practice, as a doing, and to observe it. For the house and housing biographies, our focus is therefore on different everyday activities and daily processes and movements that can be understood as exemplarily for our living practices: making tea, sitting on the sofa, entering through the door, looking out of the window; these activities are equally addressed as well as already realised practices that have spatialised and materialised, such as as the arrangement of the furniture, the decoration, the order of things in the flat or in the house. We can observe and show practices of living in houses through traces of use: the cup that still stands on the windowsill points to a favourite spot, the newspaper next to the armchair with reading light hints at how the inhabitant make themselves comfortable; the muddy boots in front of the door give proof of the walk in the woods; a fabric bag with the logo possibly points to the grocery in the neighbourhood. In a similar way, the partition of the rooms allows drawing conclusions about the living practice: how do people live together? How do they experience living together and / or in common? Are rooms, things and activities shared? A glance into the fridge should result in most flats in an overview of uses and orders, as well as relationships between the inhabitants with one another and between inhabitants and foods. It must not be underrated how difficult it is to refrain from evaluating while observing and to only record what I see and how people and things relate to one another. The best way to master this difficulty is practice. The field diary is important in this process. Notes are dated and it is possible to refer to an earlier observation or record. This way, we can enrich and add to our observations with time, until we have reached the point of saturation. It is impossible to tell from the outside when this saturation has been reached; it is for the researcher to decide that this point has been reached. The observation (like ethnography in general) doesn’t serve to produce a ‘objectively correct’ report, but to tell of the subject authentically and as close to context as possible. The intersubjective negotiation of the experience and experienced between researcher and participant is of central importance. As a result, we should show the observed person our collected material during or after the observation, as it generates questions and allows the observed person to conversely observe the observer. A reaction to a drawing or a jotted down scene can evoke associations on the part of the inhabitant on the basis of which the conversation can take unexpected turns regarding specific aspects that may have gone unnoticed otherwise.

Supporting questions

It is helpful to pose a few questions while observing with which we can attempt to grasp a seemingly simply but often increasingly complex situation: who is present? Who is not present, but perhaps in traces in the room present in their absence (e.g. strewn around toys without the child being visible or audible; a pair of large slippers by the door)? What does the person do (making tea, filling the dishwasher, opening and closing doors)? How does the person practice these things (careful, in a hurry, noisy)? How does the person relate to the situation, especially to being observed (have they tidied the place, how have they welcomed you, are they offering tea or coffee)? How is the flat / the house furnished? What does the person point out? What do they explain, and do they ask questions as well?

One’s own subjectivity in research

On the basis of these questions (that require individual expansion and must be adapted to the respective situation!) we can already recognise that the observation is always subjectively imbued and relies on subjective patterns of perception. If I happen to visit an extremely tidy or very dirty flat for a house and housing biography, it is of interest for the reflection (i.e. for the reader) to take into consideration my own position towards cleanliness. The reflexive approach has gained importance in ethnography in general (Pink 2013: 36): »A reflexive approach recognises the centrality of the subjectivity of the researcher to the production and representation of ethnographic knowledge. Reflexivity goes beyond the researcher’s concern with questions of bias and is not simply a mechanism that neutralises ethnographers’ subjectivity as collectors of data through an engagement with how their presence may have affected the reality observed and the data collected.« One’s own subjectivity must by no means be avoided or neutralised. On the contrary, it should be topicalised as a central aspect of the ethnographic knowledge, the ethnographic interpretation and representation. This includes critically thinking through one’s own disciplinary lens with which I look at the research interest. The sociologist may notice the full edition of Marx-Engels works in the shelf, and may be concluding that the inhabitant has studied social sciences and thinks critically about political economy. The architect may see at once the breakthrough of the wall that the inhabitant or someone else must have done themselves. She may be concluding that the renovation was undertaken without professional help. A furniture designer would look at the furniture and recognise that the inhabitant has a soft spot for a specific style or designer. All these observations can provide an insight about the living practice of the inhabitant; these can perfectly well be different or complementary conclusions – as long as one’s own perspective is reflected and recognised in the observation, it can help to enable particular observations in the first place, ones that wouldn’t take place without this »lens« at all. At this point it is therefore important to stress the enrichment of interdisciplinary work: Working in interdisciplinary groups allows for a discussion about the individual observations to be had during the research phase, which can lead to new connections and questions. This equally explains that survey and interview can only lead to limited results in the house and housing biography, if it isn’t supplemented with observations (cf. Spittler 2001: 8). Had we only interviewed the inhabitant, they could well refrain (unconsciously) from mentioning many aspects that are of great interest to the research project, just because these aspects will only surface in the dialogical conversation. Only if I address seeing the Marx-Engels works will I find out whether their political-philosophical position has meaning (for them) in their living practice; only if I mention the breakthrough in the wall, can they tell me that it had already been done when they moved in or, alternatively, that they did it themselves with the help of some friends.

Howard Becker (2009) describes how he started to make observations as a child and how he strengthened and systematically used this perspective as a (grown-up) ethnograph. His account also makes clear that the observation of the living practice doesn’t start or end at the door. We attempt to always acknowledge and bear in mind the three analytical levels house, block/neighbourhood and city that can themselves produce conclusions. Becker describes in his short text »Learning to observe in Chicago« (2009) vividly how he spent whole afternoons as a child on the El Train (Elevated train system in Chicago) and observed from the window the city, the subsequent neighbourhoods and – wherever the houses stood near enough to the tracks – the flats and inhabitants:

»What did we see? We saw the buildings and how they varied from place to place: the poor deteriorating wooden apartment buildings in the city’s poorer neighbourhoods; the multi-story brick buildings in neighbourhoods that were more well to do; the one family houses of some ethnic neighborhoods; and so on. We learned the characteristic ethnic patterns of the city by reading the signs on the businesses we went by and learned that the Poles lived on Milwaukee Avenue, the Italians on the Near West Side, the Swedes farther North, the Black on the South Side, and so on. We saw people of different racial and ethnic groups as they got on and off the train, and learned who lived where (we were very good at reading ethnicity from small clues, including listening to the languages spoken, styles of clothing, even the smell of the food people carried). [...] We saw things close up as well as from a distance. As all these people got on and off the cars we rode in, we knew we were different from many of them – racially different, different in class, different in ethnicity. [...] In many of the places the trains went through, the buildings were very close to the tracks, maybe no more than five feet away, and the windows in the buildings looked out directly on to the tracks. So we could look into people’s apartments and watch them going about the ordinary routines of apartment living: making and eating meals, cleaning, doing laundry, sitting around listening to the radio and drinking coffee, women doing each other’s hair, kids playing. [...] This gave us a lot of material on differing ways of life to think about.« (Becker 2009: n.p.)

The BURANO group developed a method to capture, to represent and to mediate socio-economic aspects (society and economy), built forms (building structure and designs) and communication (interpersonal relations) in their interaction. This observation method is an appropriate tool for house and housing biographies in order to integrate the analytical levels block/neighbourhood and city in our assumption that living practice doesn’t begin or end at the door. The group mapped spatial activities in different places and on various squares, held interviews with residents, read maps and plans together and produced snapshots at different times in which activities (walking, standing, playing, talking) were related to invariables (spatial situations and their characteristics). Using the results of these observations we can also penetrate larger neighbourhoods and relations within the city and its fabric. Bringing these into relation with the house and housing biographies helps to enrich the latter in the sense that single living situations can be related to their context.

Lizence: CC BY-NC-SA

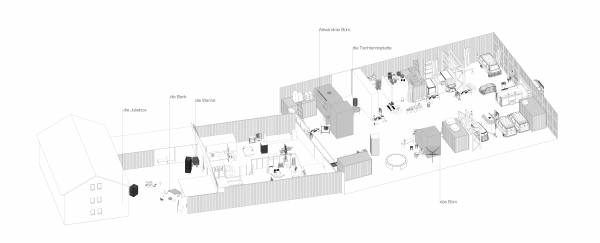

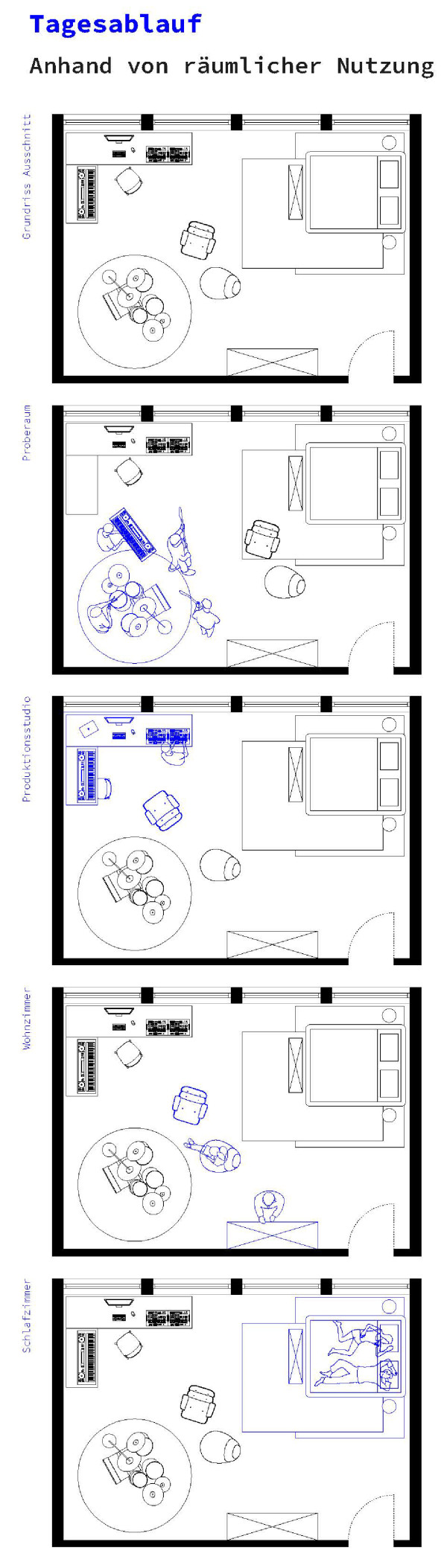

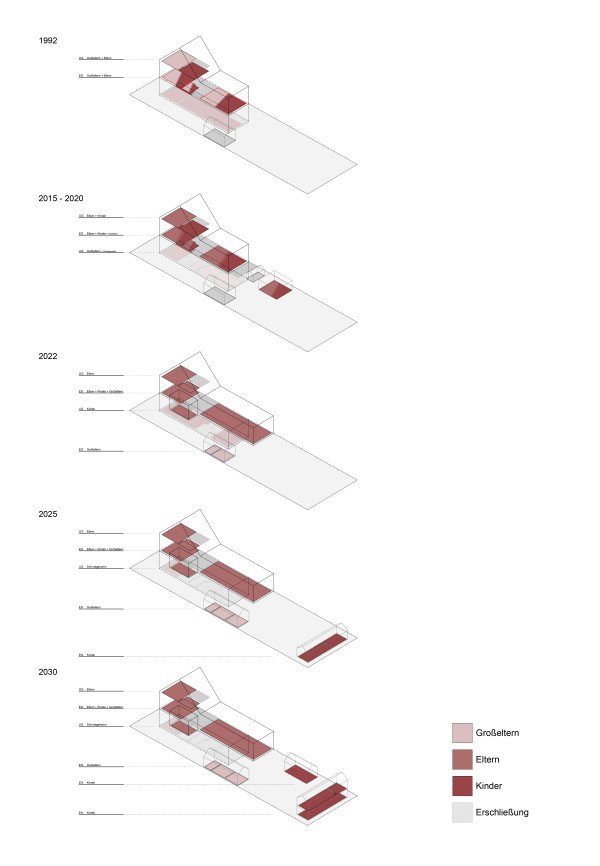

Zeitstrahl der Flächennutzung

Seriell-Individuell - Wohnzimmer

Als spezifische Raumfunktion wählen wir für unseren Fall das Wohnzimmer. Das Wohnzimmer ist nicht nur dahingehend interessant, dass es als der zentrale Wohnraum im Mittelpunkt der Orientierung liegt, sondern auch, dass er mittlerweile, jedenfalls im Kontext der bürgerlichen Kleinfamilie, der sozialste aller Räume innerhalb der Wohnung, im Gegensatz zum Individualraum, ist. …

Continue reading...

Open | Closed | Ajar - Analysis

Variable spatial functions for flexible living arrangements?

_»When you build a house, the first resident is the client; perhaps other people move in and live there after twenty years. When I design and plan a house, today I work with rooms that I don’t define closer; they can be used differently and how they will be used is determined by how the inhabitants use them, wha…

Continue reading...

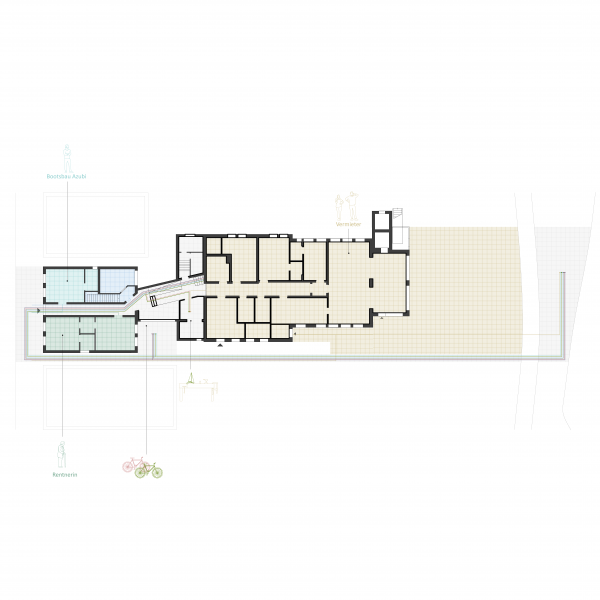

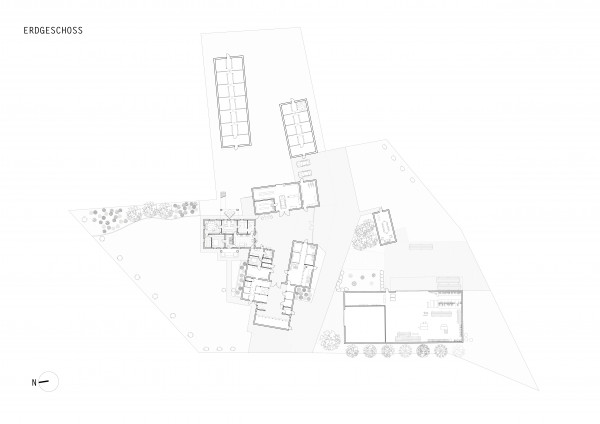

Steckbrief

Lage: Grundstück in einer kleinen Stadt am Fluss

Nutzung: Wohnen und Arbeiten

Frühere Nutzung: Altenheim

Gebäude: Zweigeschossiges Vorderhaus im direkten Verbund mit zweigeschossigem Hinterhaus

Wohneinheiten: 9

BewohnerInnen: 13

BewohnerInnen und Größe der jeweiligen Wohneinheit:

Vermieterehepaar: arbeitendes Ehepaar mittleren Alters, ca. 292m² Wohnen im EG und Arbeiten im OG…

Steckbrief

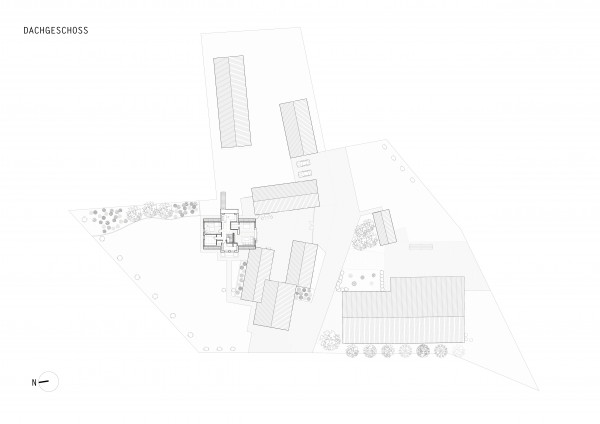

Lage: Grundstück am Rande eines kleinen Dorfes

Nutzung: Wohnen

Grundstück: ca. 2.400m²

Bebaute Fläche: ca. 112m² (+ 166m² Scheune)

Wohngebäude: Zweigeschossig + Dachgeschoss und Kellergeschoss

Wohneinheiten: 2

Bewohner*innen: 3

Baujahr: 1912

Umbau: 1967, 2009

Bewohner*innen:

Eine Seniorin im Erdgeschoss, ihr Sohn und dessen Ehefrau mit 2 Hunden im Obergeschoss und 6 Hühnern im…

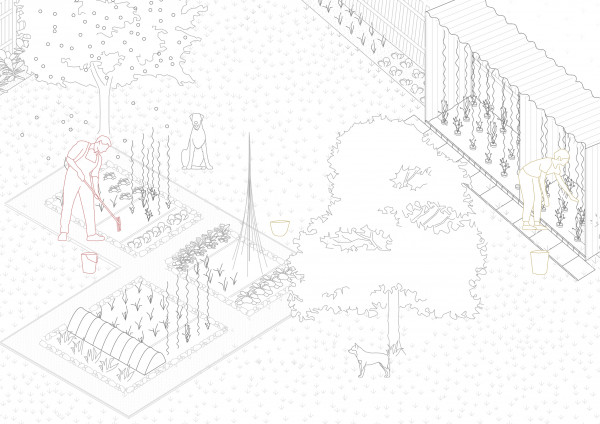

Leben mit den Jahreszeiten

Die beschriebene Wohnsituation von B. verdeutlicht, dass Wohnen nicht ausschließlich durch die Innenräume eines Hauses definiert ist, sondern stets eine Verbindung zum Außenbereich aufweist, da grundlegende Bedürfnisse wie Zugang zu Wasser oder Toilettennutzung nur durch den Außenraum möglich sind. In B.s Fall ist das Wohnen im Kleingarten stark von Witterungsbedingungen abhäng…

Continue reading...

"Also ich könnte das ja nicht"

Das ist ein Satz, den alle Bewohner:innen der Funktionalen Wohngemeinschaft (FuWo) schon unzählige Male von ihrem Umfeld gehört haben. Doch was genau können diese Leute nicht? Kannst du das lernen oder braucht es bestimmte Charaktereigenschaften um in dieser Wohnform leben zu können? In der FuWo teilen sich die Bewohner:innen fast alles: Essen, Kleidung sowie die Räume. Mit fü…

Continue reading...

1. Akt: Prolog - Wohnen und Arbeiten auf Theaterbühnen

Vertiefung

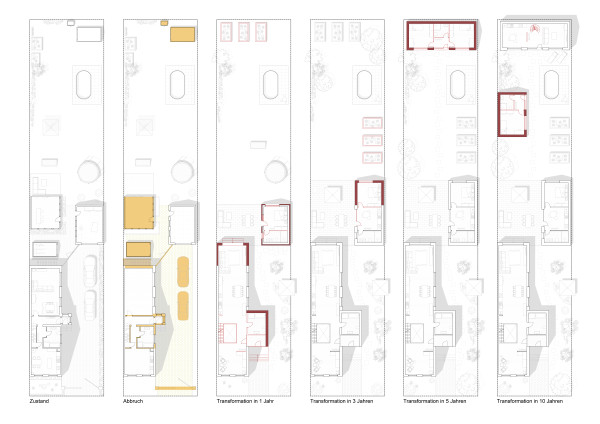

Herr G wohnt mittlerweile seit 23 Jahren in einem auf dem Land gelegenen Diensthaus für Beamte. Während dieser Zeit haben sich immer wieder Veränderungen im Leben ergeben, die sich in der Nutzung der Wohnfläche widerspiegeln (siehe Zeitstrahl). Mit Eintritt in die Pension, erlischt auch das Wohnrecht in diesem Haus. So ist es nun soweit, dass der Umzug in eine neue Wohnung bevo…

Continue reading...

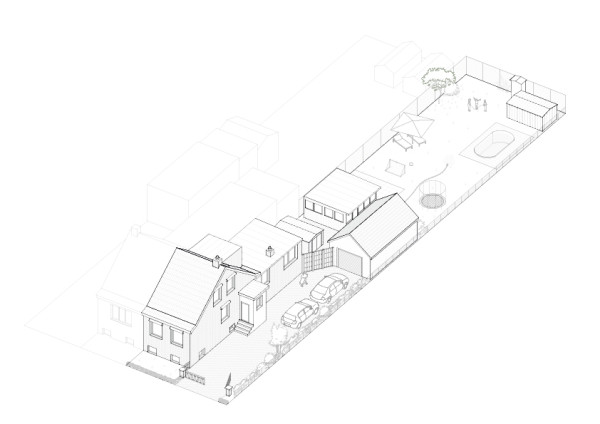

Zug um Zug – Isometrie innen

The Rules Do Not Apply – Kurzbeschreibung

For seven years Mr. U. has been working and living in and around the factory building where his residential studio is located. The old factory, once a large ensemble and the site of the processing of large quantities of vegetable fat, is now only partly standing. From the street it looks run-down, in the recognizable openings of old industrial windows there are provisionally ap…

Continue reading...Wohnatelier einer Hutmacherin – Kurzbeschreibung

Seit knapp 30 Jahren arbeitet Herr F., der gelernter Illustrator und Grafiker ist, in dem Ladenatelier, in einem zentralen Bezirk von Hamburg. Seit gut zehn Jahren wohnt er auch dort. Vor ihm lebten und arbeiteten eine Hutmacherin, ein Fotograph, und ein Übersetzer in dieser Wohnung mit Ladenatelier. Die Hutmacherin zog als erste Mieterin 1953 in das Haus ein. Bis heute gehört …

Continue reading...

Eigentumsformen und Beziehungsweisen

Die Reaktion „ich könnte das ja nicht“, auf die wir in Zusammenhang mit dem Fall der Funktionalen WG gestoßen sind, zeigt, wie stark Vorstellungen des Wohnens gesellschaftlich verankert und unhinterfragt sind. Viele Menschen können sich nicht vorstellen, dauerhaft mit anderen einen Raum zum Schlafen zu teilen, und keinen „eigenen“ Raum zu haben, den man für sich allein hat und …

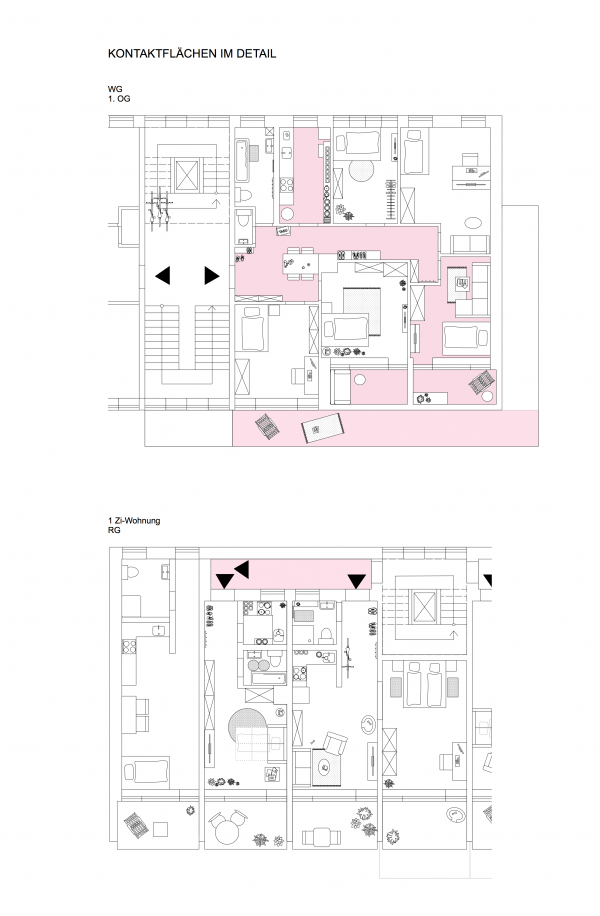

Continue reading...Kontaktflächen Heute & Morgen

In Anbetracht der Theorie des Raumes von Henri Lefebvre (1967) verstehen wir den Raum als relationales Produkt. Hierbei wird das Wohnen als sozialräumlicher Prozess kontinuierlich durch wechselseitige Beziehung sozialer, ökonomischer, politischer und kultureller Praktiken hergestellt. Menschen, Objekte, Regelwerke und Materialitäten bilden hierbei das Beziehungsgefüge des Wohne…

Continue reading...

Familiengeschichten - Szenario: Scheune

von 390 m² auf 130 m²

130 m2 pro Haushalt. 130 m2 pro Kopf Wohnfläche. So leben Ella in der mittleren Wohnung des dreistöckigen Hauses und die Bewohnerin in der Dachgeschosswohnung. Das Ehepaar im Erdgeschoss teilt sich die Fläche, wobei sie eine Pro-Kopf-Wohnfläche von 65 m2 einnehmen.

Die drei Wohnungen wurden unabhängig voneinander zu verschiedenen Zeitpunkten vermietet und sind jeweils von den …

Continue reading...

Klein aber fein – Film

Gruppenraum

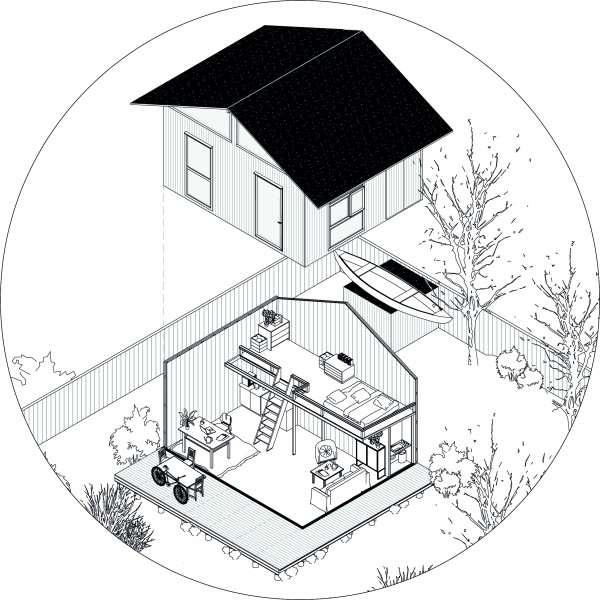

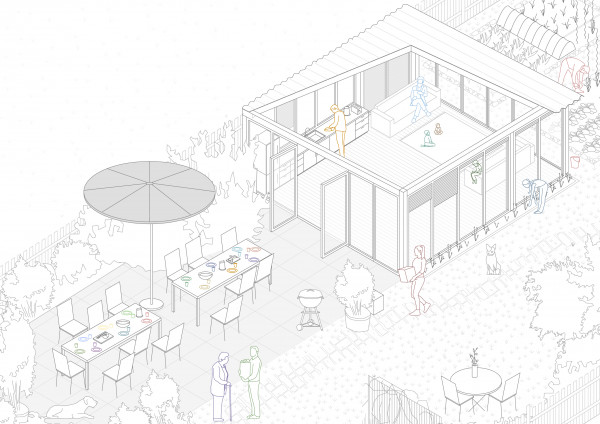

Familiengeschichten - Szenario: Wohnen im Garten

Familiengeschichten - Grundrisse heute mit Interviewzitaten

Seriell-Individuell – Film

Seriell-Individuell - Vertiefung

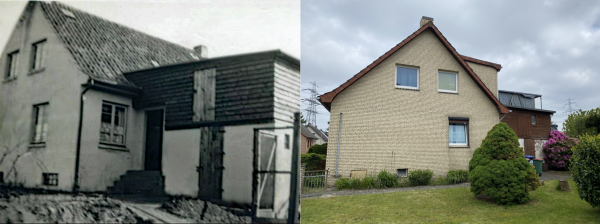

Familie K., im Jahr 1986 noch zu zweit, erwirbt damals das Einfamilienhaus in Volksdorf im sanierungsfälligen Zustand: Es handelt sich um eine Doppelhaushälfte aus dem Jahre 1930, entstanden als eines von 120 typgleichen Doppelhaushälften im Rahmen der Siedlungsbebauung "Schwarze Wöörden" der Siedlungsgenossenschaft Volksdorf.

Volksdorf bietet als nordöstlicher Stadtteil…

Versorgungsmöglichkeiten

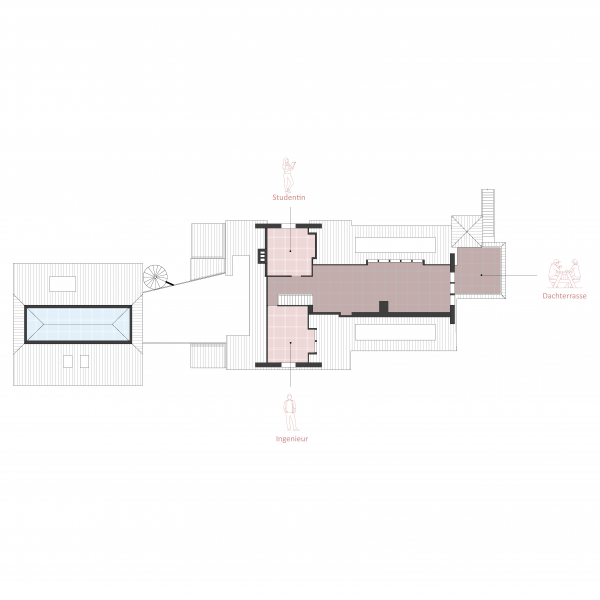

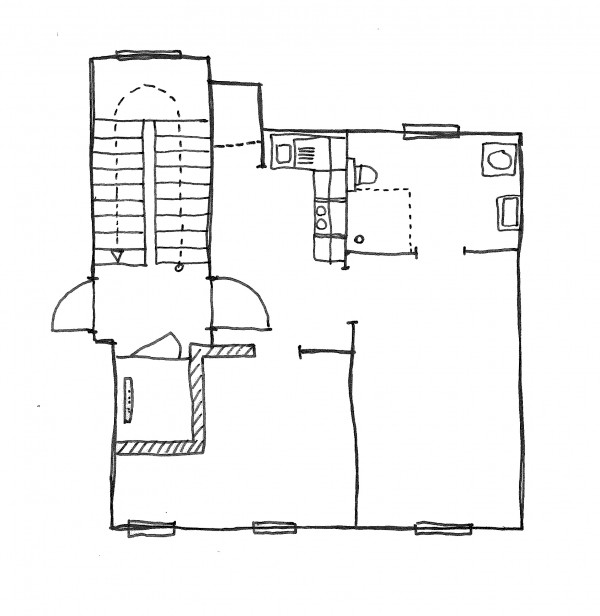

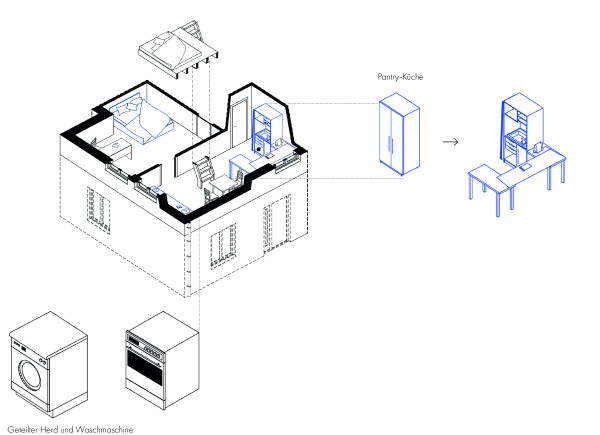

Zug um Zug - Kurzbeschreibung

Vor einem Jahr hat Julia ein neuen Raum in einer Ateliergemeinschaft gefunden. Das Gebäude einer ehemaligen Fliesenlegerberufsschule liegt im Osten Hamburgs und beherbergt seit mehreren Jahren Gewerbefläche im EG und die Ateliergemeinschaft im 1OG.

15 Räume dienen der heterogenen Gruppe verschiedenster Künstler*innen als Arbeitsplatz. Häufig werden die 65qm großen Ateliers…

weichblich, alleinstehend, 60+ – Film

Familiengeschichten - Szenario: Gartenlaube und Terrasse

Familiengeschichten - Szenario: Obst- und Gemüseanbau

Zug um Zug – Film

Auf-Zu-Angelehnt - Film

female, living alone, 60+ – Analysis

Intro

”I like it a lot, living here. We have everything we would want. And it’s possible to take the courage and ring at Ms. X’s door, whom you don’t know well at all, and say: Let’s have a coffee. We meet in the garden. The women visit each other, if they are closer. We can be alone. And we are always safe, when someone doesn’t feel well.” (Felka)

The German society ag…

Living and working under the same roof – Analysis

Mr and Ms B’s flat

(1) Flat for the master joiner

Not subject of this research; Access through the staircase

(2) Ludwig and Helene B’s Flat

This flat has been the couple’s home since 1962. It is furnished with attention to details with lots of wood and fabric in the style of the 1970s.

(3) Via an L-shaped corridor, you enter into the heart of the flat: a warmly furnished k…

Continue reading...

Vertiefung

Gemeinschaftliches Zusammenleben spielt im Fall „Familiengeschichten“ eine zentrale Rolle. Anhand der unterschiedlichen Konstellationen, in denen hier über die Jahre zusammengewohnt wurde, konnten verschiedene Formen von Wohnen in der Gemeinschaft betrachtet und aus positiven wie negativen Aspekten Schlüsse für zukünftige Wohnformen gezogen werden.

*Wie hat sich das Wohnen un…

Continue reading...Familiengeschichten - Katalog Wohnqualitäten

Der Garten und die Wohnpraxis

Die Größe des Gartens, ein schmales rechteckiges Grundstück in der zweiten Reihe vom Hauptweg des Gartenvereins, beträgt 400 ㎡. Mittig des Grundstücks steht das Gartenhaus, es ist 24 ㎡ groß und besteht aus Lärchenholz. Das Haus ist isoliert, mit einer Außen- und Innenwand. Eine wichtige und zentrale Eigenschaft, die das Wohnen hier möglich macht. Der Wohnbereich der Hütte ist u…

Continue reading...Vertiefung - Brüchige Nachbarschaft

Der Hof ist ein merkwürdiger, ein verrückter Ort. Die räumlichen und sozialen Eigenschaften, die sich an diesem Ort überlagern, unterstützen und behindern sich zugleich, sodass nicht direkt ersichtlich ist, welche Qualitäten sich für den Raum daraus ergeben.

*Warum kommt bei den Bewohner:innen kein wirkliches Gefühl von Gemeinschaft auf, obwohl die Lage an dem privaten Hof doch…

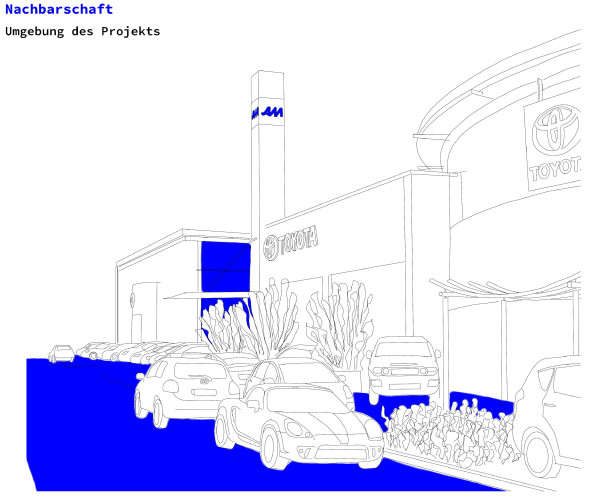

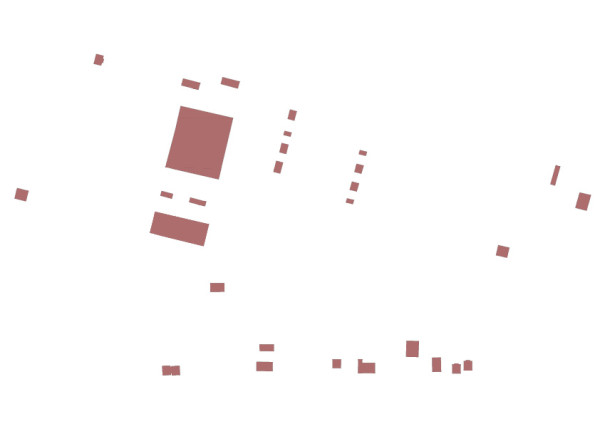

Städtebauliches Umfeld

Mitten in einer Großstadt, nicht weit vom Zentrum und den umliegenden Gewässern entfernt, verläuft eine der Haupterschließungsstraßen der Stadt. Der Verkehr ist dicht. Neben der S-Bahn, den separaten Fahrradspuren und Fußwegen, befindet sich eine vierarmige Kreuzung mit jeweils drei Spuren pro Fahrtrichtung. Das einzige Grün in Sichtweite sind die angelegten Grünstreifen und Bä…

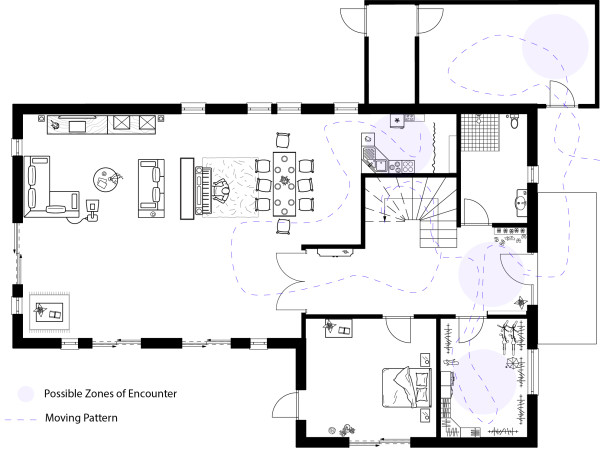

Continue reading...Open | Closed | Ajar - Short description

For thirty-five years, tenant Frieda has lived in her flat in the late-nineteenth century tenement building in the centre of Hamburg, in very different constellations. The various phases in her life meant that she and her respective flatmates had changing demands regarding her usage of the flat, which was and is expressed in the flexible appropriation of the rooms on the part o…

Continue reading...

Hotel Mama + Papa – Vertiefung

Das Haus wurde zu anderen Zeiten auch schon von vier verschiedenen Familien bewohnt, diente als Bäckerei und auch als Herberge zur Heimat für umherziehende Handwerker. Der Herbergen-Charakter kehrt nun durch das Bereithalten der Gästezimmer für die Kinder wieder. Häufig komme es dazu, dass ein Kind übergangsweise wieder einziehe, wie z.B. eine Tochter, die nun hier wohne, solan…

Continue reading...

Wohnen und Arbeiten - Film - Melling/HCU 2019

Ortsbesichtigungen

Erste Ortsbesichtigung

Am Samstagvormittag steigen wir in den Zug und werden am Bahnhof mit dem Auto eingesammelt, um gemeinsam zum Standort zu gelangen. Aufmerksam achten wir auf die Navigation, damit wir die entsprechenden Ausfahrten und Abbiegungen nicht verpassen. Angekommen in der Siedlung geht es in Schrittgeschwindigkeit in eine der drei engen Gassen, in die gerade…

Continue reading...

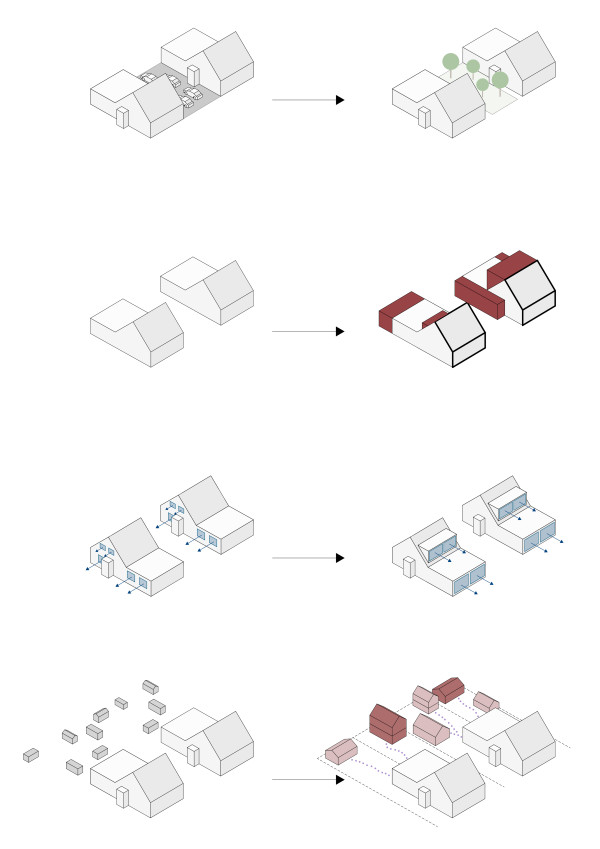

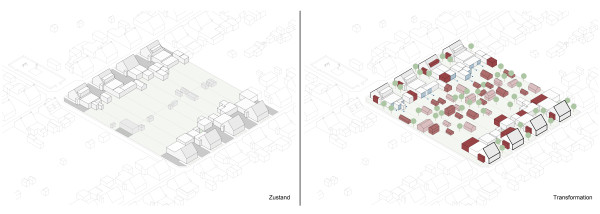

Transformation

In dem ausgewählten Projekt „Die verloste Siedlung“ haben wir im Laufe des Seminars unseren Fokus auf die Historie und Abwandlung des Hauses mit Blick auf die Familiengeschichten gelegt. Mit den geführten Gesprächen der Familie und die vielen Ortbesuche rückte immer weiter die Frage in den Vordergrund ´Wie wird eigentlich gewohnt? ´

Die Schwiegereltern wohnen aktuell im Unte…

Continue reading...

Wand an Wand – Film

Einblick in den Garten

Beschreibung der Wohnsituation

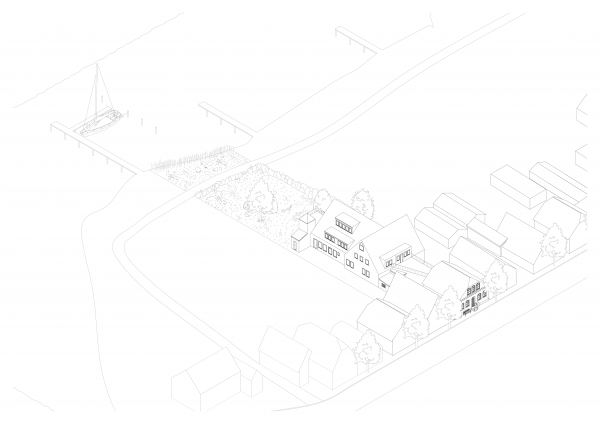

Das Gebäude liegt in einer kleinen Marktgemeinde ca. 12 km von einer süddeutschen Universitätsstadt entfernt. Die Bevölkerungsdichte entspricht hier ca. 157 Einwohner je km². Der Standort befindet sich außerhalb des eng bebauten Ortskerns an der Hauptstraße, die den Ort durchquert und parallel zur Bahntrasse verläuft. Die Bebauungsstruktur ist hier aufgelöst, freistehende Häuse…

Continue reading...Living and working under the same roof – Short description

The couple B lives and has worked under one roof in their carpentry on Hamburg’s fringes. Their house allows to observe how social structures and economic working processes have influenced the architecture of a workshop more than half a century ago and how it can be transformed and re-used over the course of time. This house contains one room, for instance, that was built adjac…

Continue reading...

Geplante Gemeinschaft - Vertiefung

Von außen betrachtet fügt sich der untersuchte Gebäudekomplex mit seiner gefliesten Fassade baulich gut in die umgebenden Backsteinaltbauten ein, sticht als Wohngebäude in dem von Büros dominierten Quartier jedoch heraus. Im Erdgeschoss befinden sich ein Kiosk und ein Restaurant – mittags ist hier Rushhour. Dann beleben die Menschen, die in den umgebenden Bürogebäuden arbeiten,…

Continue reading...

1932-2021

5. Akt: Blick in die Vergangenheit...für den Wurf in die Zukunft!

Seriell-Individuell - Kurzbeschreibung

Die Doppelhaushälfte der Familie K. in Volksdorf ist Teil einer Siedlungsbebauung der 1930er Jahre. Katalogartig werden die jeweils individuellen Erweiterungen fast aller Häuser in der Siedlung dargestellt; vertieft wird diese Entwicklung am Beispiel der Familie K. Die Arbeit zeigt die sich verändernden Raumvorstellungen im Laufe der Zeit: Während zur Zeit der Fertigstellun…

Continue reading...

Vertiefung: Das gemachte Nest der Moderne

*„Weite Kreise der Berufsfrauen leiden seelisch unter der Wohnungsnot. Für viele alleinstehende Damen bedeutet die Erlangung eines eigenen Heimes die Erfüllung eines letzten Ideals. Die Frau, die im Geschäft, Schule, Amt, Büro oder sonstwo tagsüber ihre Berufspflicht erfüllt, braucht nicht nur ein gesundes, sondern auch ein behagliches Heim, in dem sie nach des Tages Last wiede…

Continue reading...Mögliche Umnutzungen

Zeitstrahl der Flächennutzung

Zug um Zug – Isometrie außen

Pharmacist’s house – Analysis

The pharmacy has existed here since 1724. The family has owned it since 19145 when Ms A’s great grandfather bought it. There have been some changes to the building in order to react to changing requirements and demands. The 1970s saw a legal regulation come into force that requires that the pharmacy is spatially strictly separated from rooms in the house that are used otherwise…

Continue reading...The Rules Do Not Apply – Analysis

"Anyone who painstakingly renovates something dilapidated is driven by fantasies that are stronger than any reality. All good reasons for what is necessary, practical and economical fade away or are subordinated to the decision to invest infinite effort " (Selle 1993: 25f).

Mr. U. came to the room that is now used as…

Continue reading...

Beschreibung der Wohnsituation

Das malerische, weiße Häuschen mit blau umrahmten Fenstern liegt in einer kleinen Stadt direkt an einem Fluss. Durch einen langen Flur wird es mit seinem gelben Hinterhaus verbunden. Tür an Tür reihen sich die verschiedensten Wohnsituationen aneinander.

In dem Vorderhaus wohnt im Erdgeschoss eine Rentnerin, deren 2-Zimmerwohnung zur rechten Seite des Flures zu betreten ist. Au…

Wohnatelier einer Hutmacherin – Vertiefung

Mir persönlich gefallen einige Dinge an der dichten Verbindung von Arbeiten und Wohnen. Für mich ist die Ruhe der Wohnung als Rückzugsort, die freie Organisation und die Möglichkeit des schnellen Wechsels von verschiedenen Tätigkeiten ein Vorteil, wenn der Wohnort auch gleichzeitig die Arbeitsstelle ist.

Gleichzeitig fehlen mir durch die gleichen Vorteile auch Abläufe in mein…

Direkt am Kanal – Vertiefung

2005 habe Herr D. das von 1880 stammende Gebäude erworben, nachdem der Vorbesitzer insolvent gegangen sei und das Haus zwangsversteigert werden musste. Im dreigeschossigen Hauptgebäude habe es zu diesem Zeitpunkt drei separate Wohneinheiten gegeben. Zwei im Erdgeschoss, welche jeweils aus zwei Zimmern, Pantryküche und einem Bad bestanden, und eine Wohneinheit im zweiten Oberges…

Continue reading...Folglich braucht Wohnen...

-Kollektiven Besitz / Soziales Netzwerk

-Kleine individuelle Privaträume als Rückzugsorte für Bewohner*innen

-Zwischengeschaltete Flächen als kollektive Räume für Zusammenleben

-Gemeinschaftliche Innen und Außenflächen, die auch über die Wohngemeinschaft für Gäste und Öffentlichkeit geöffnet werden können

-Wasser/Pool als zentrales Element der Begegnung

-Keine Begrenzung der ma…