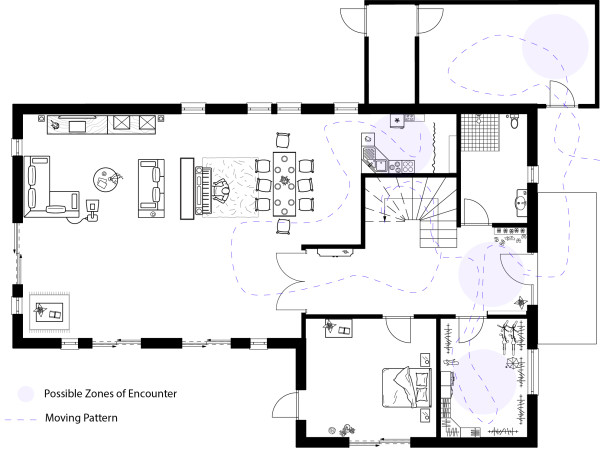

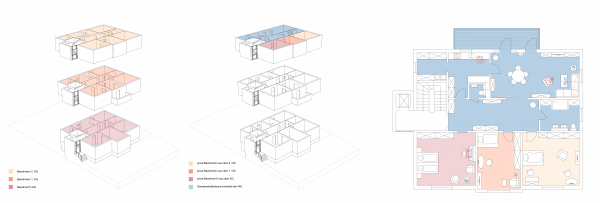

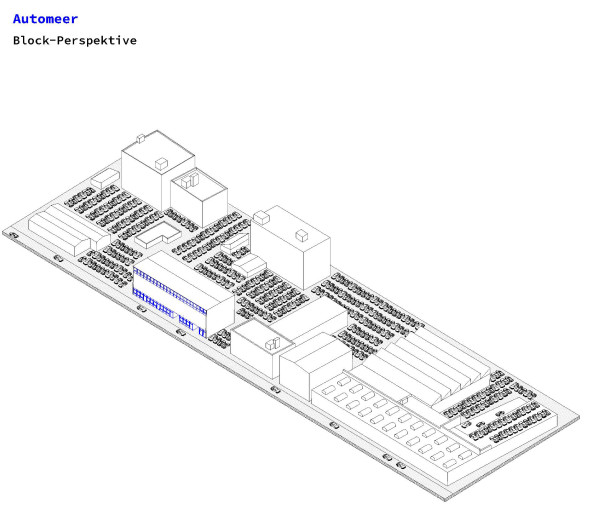

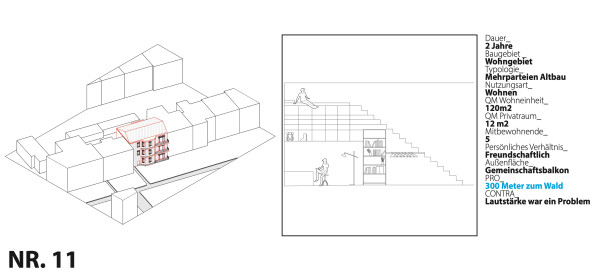

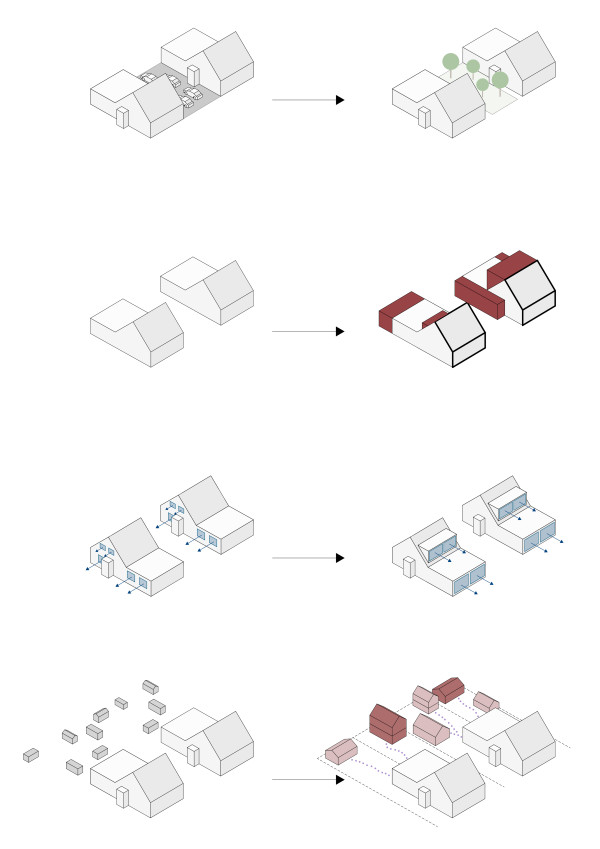

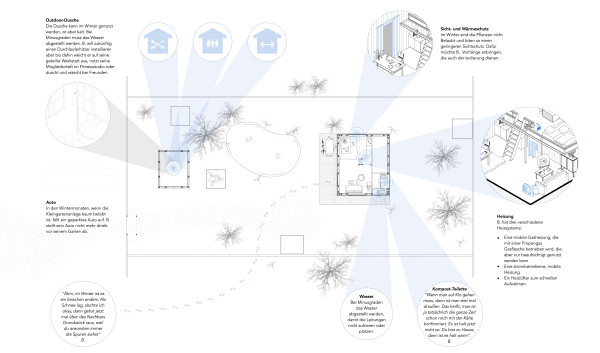

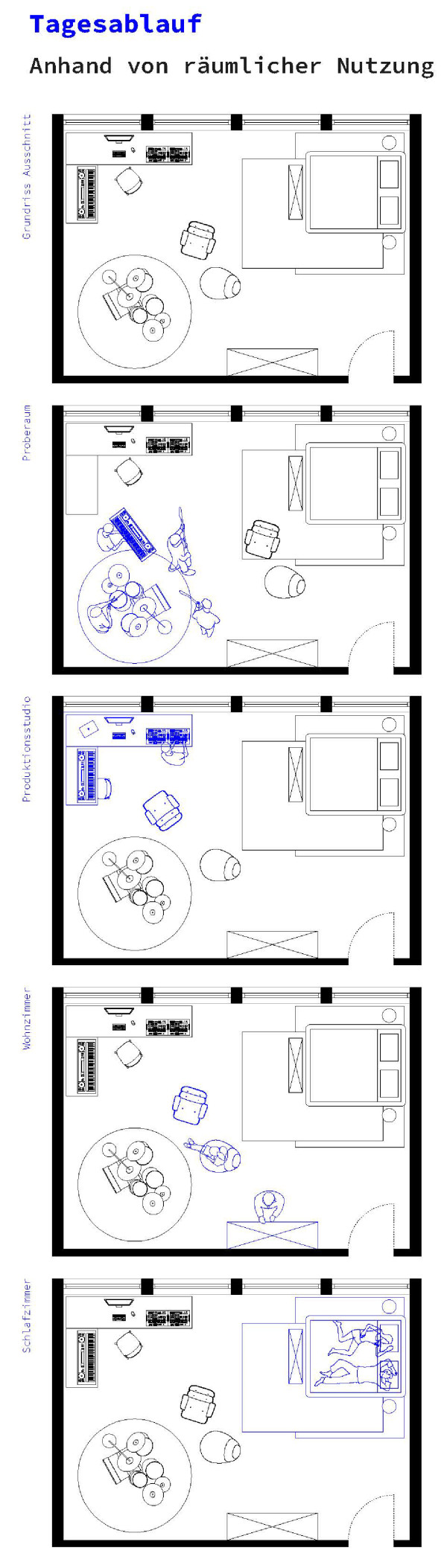

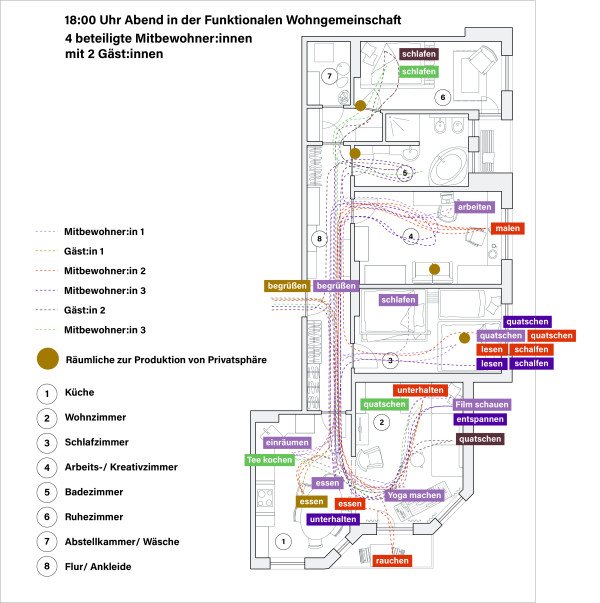

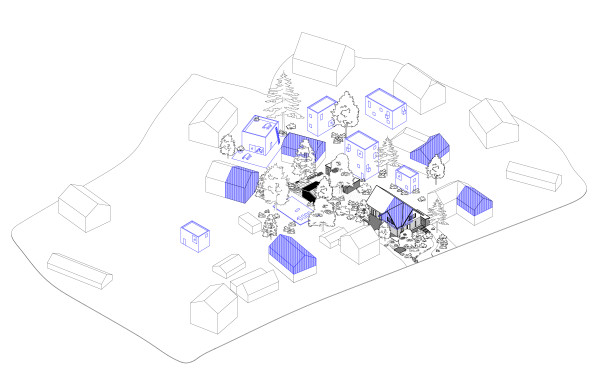

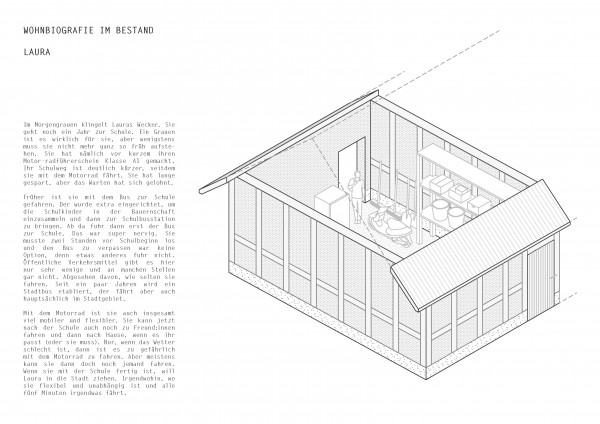

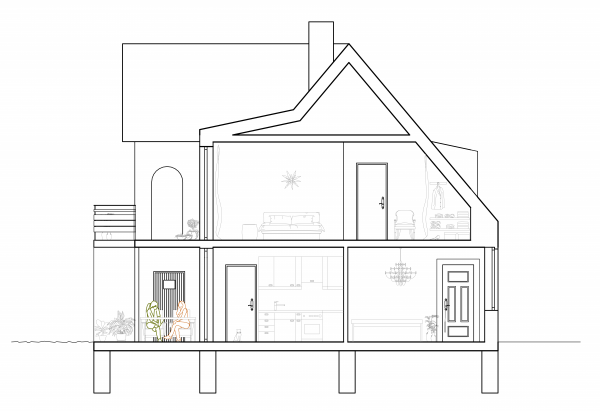

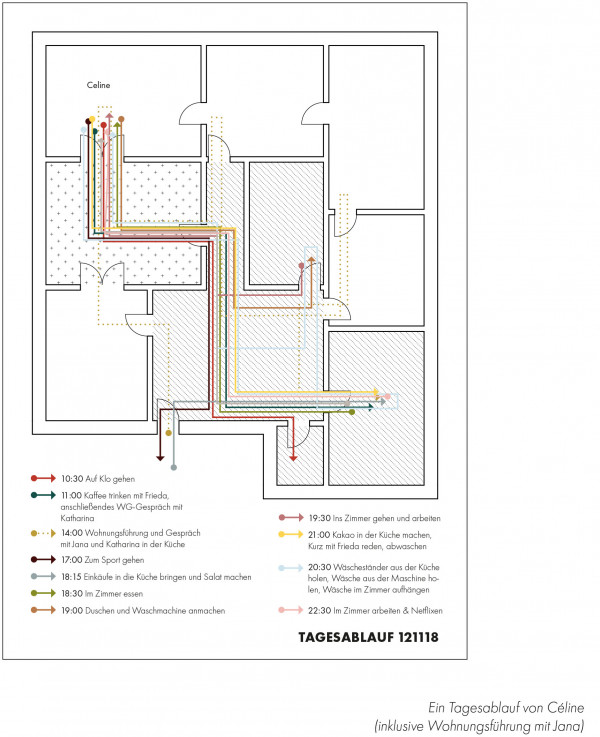

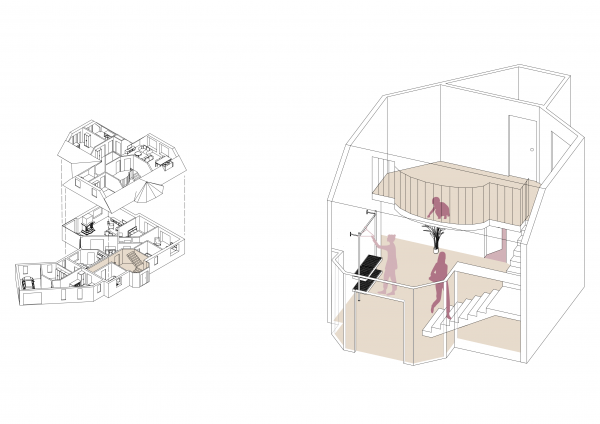

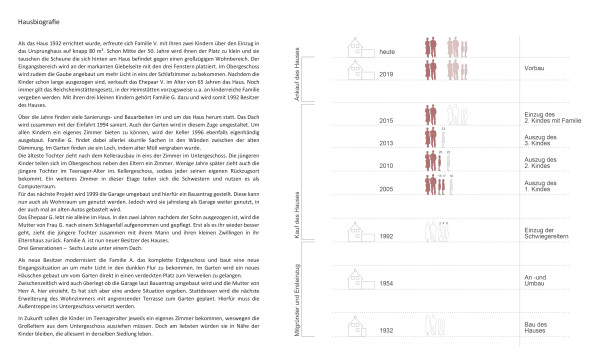

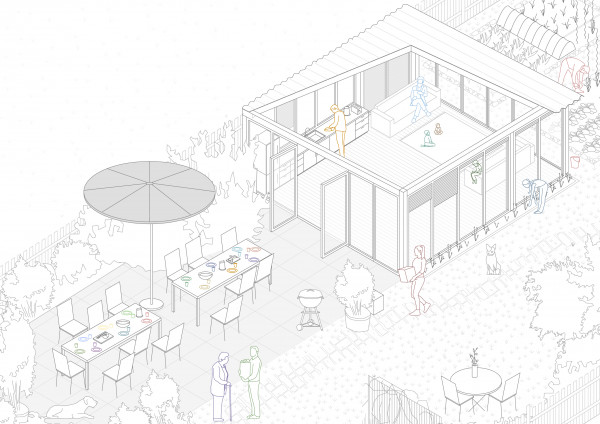

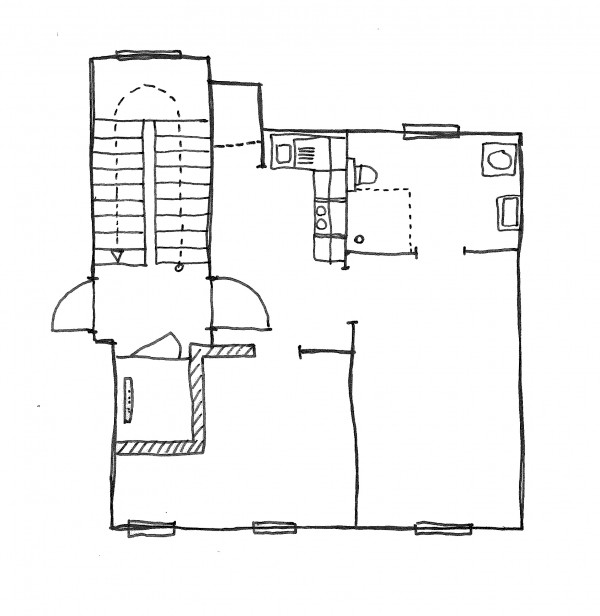

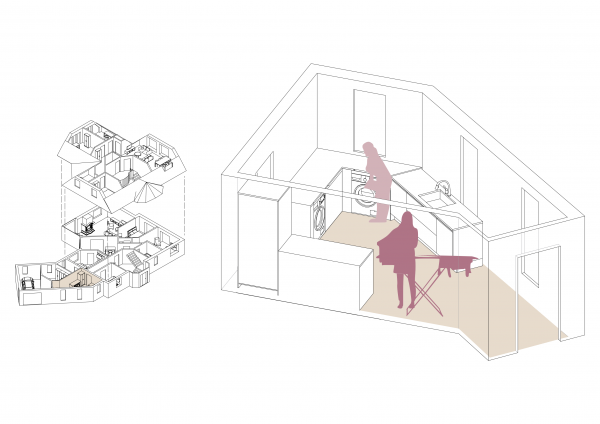

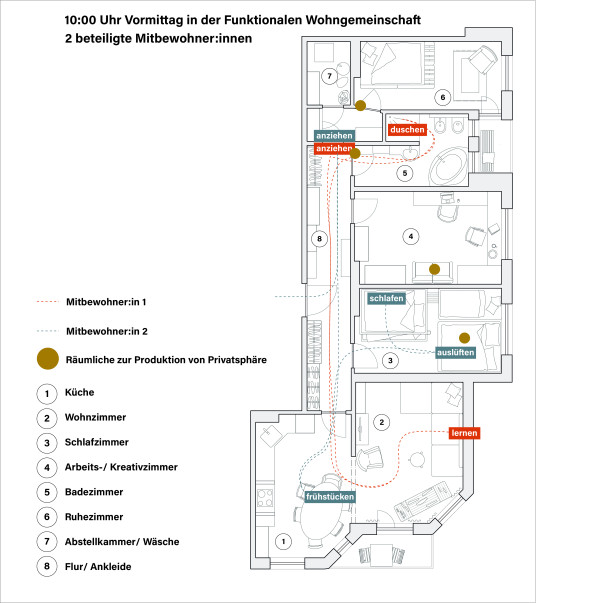

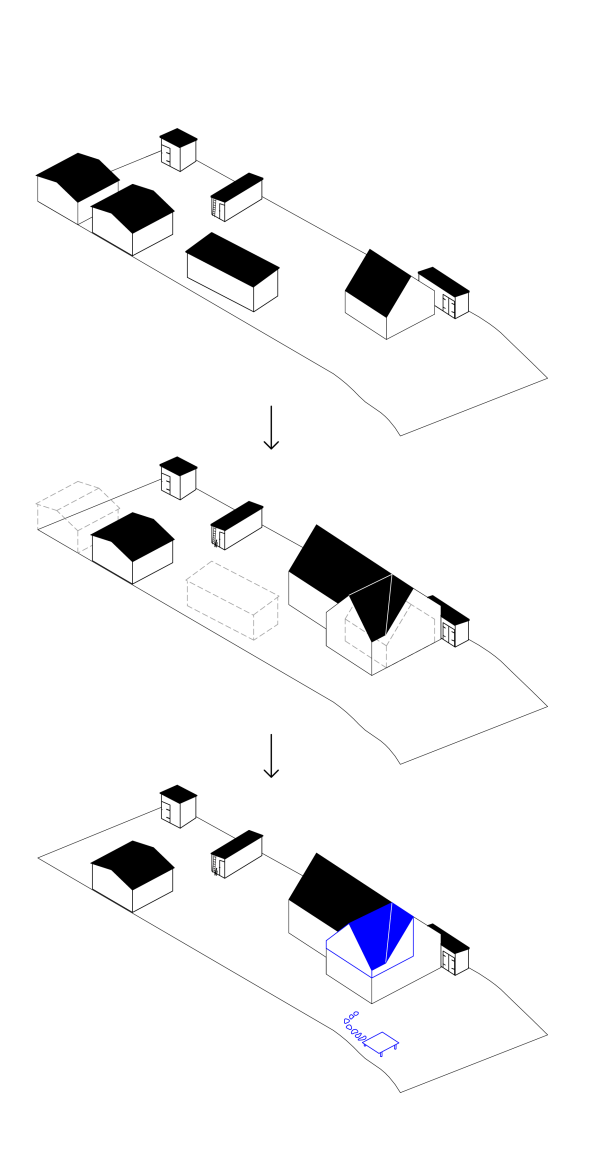

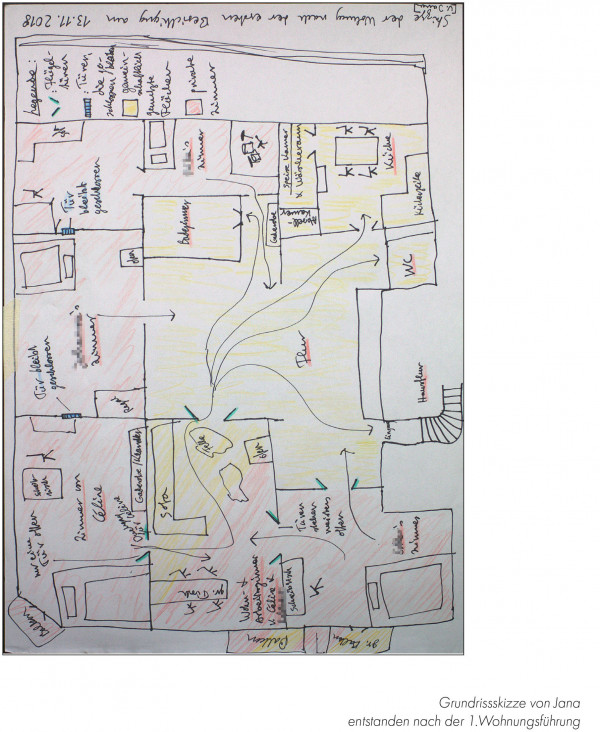

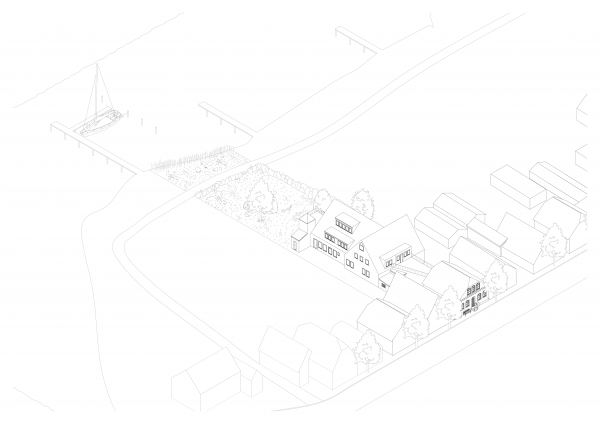

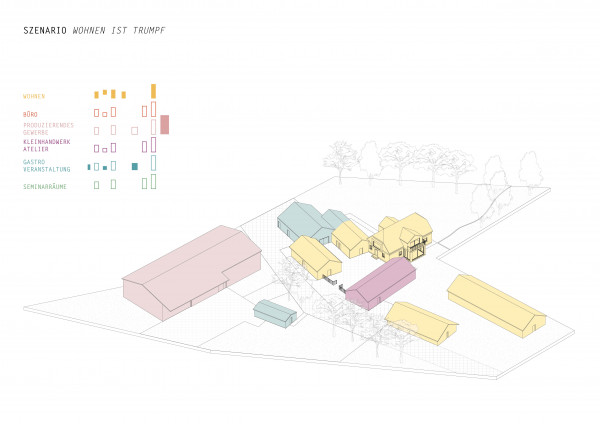

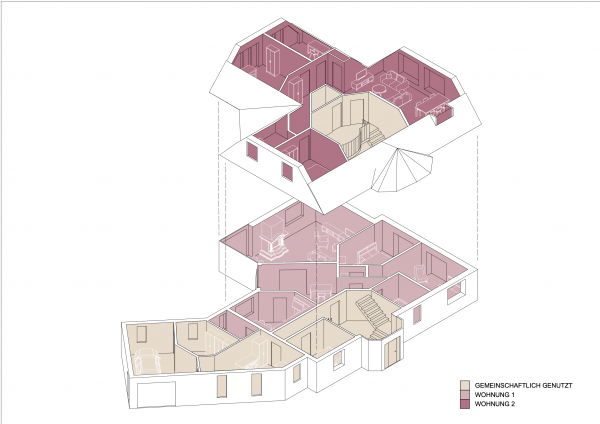

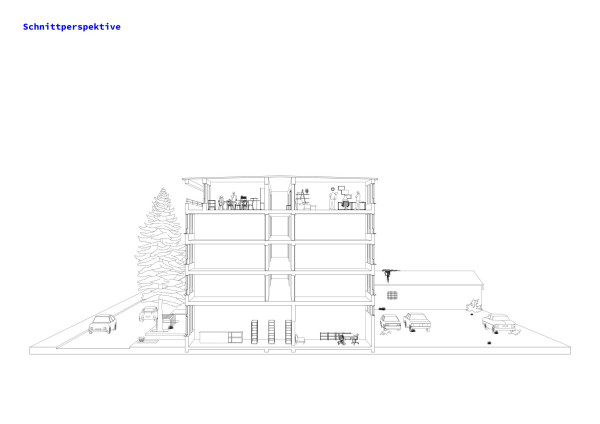

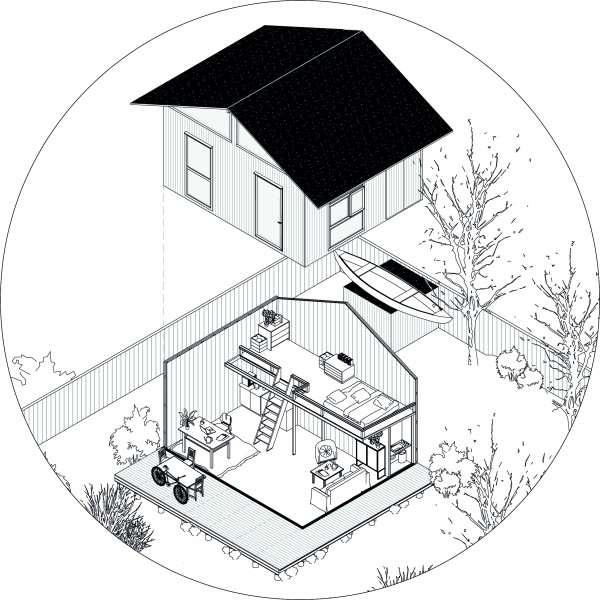

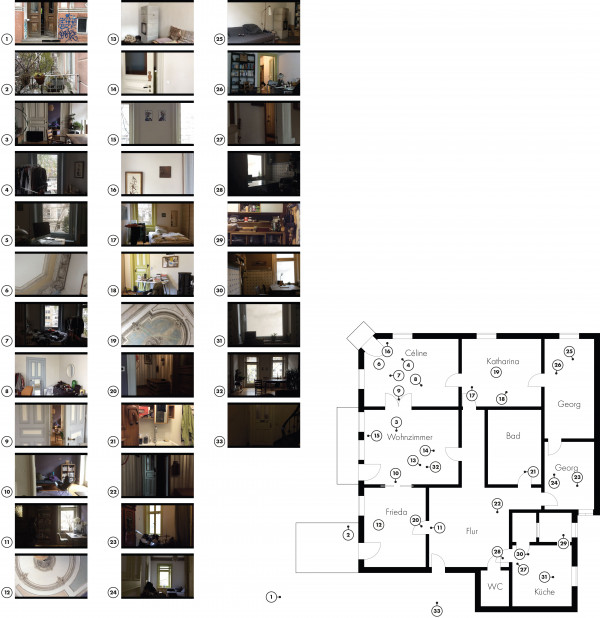

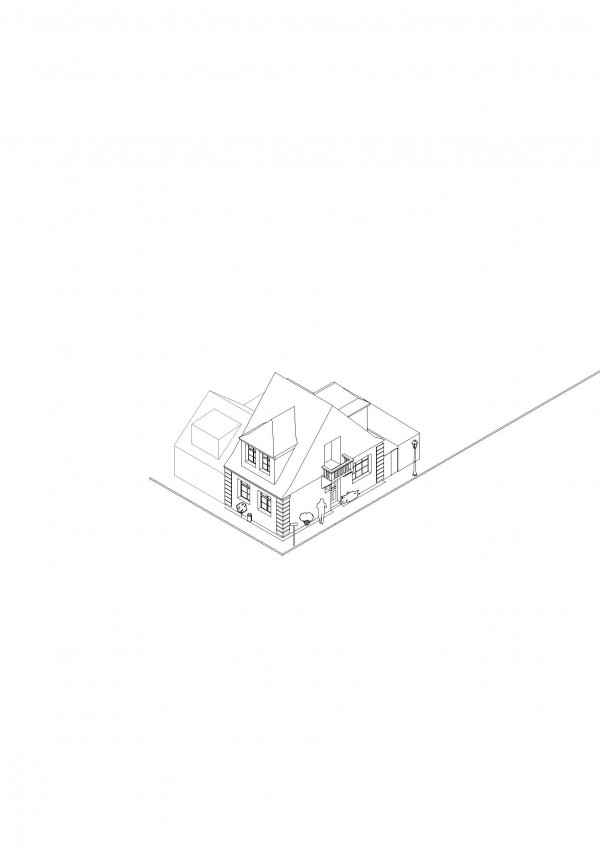

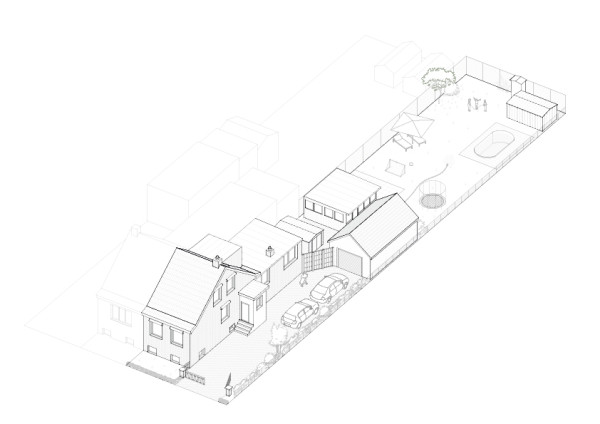

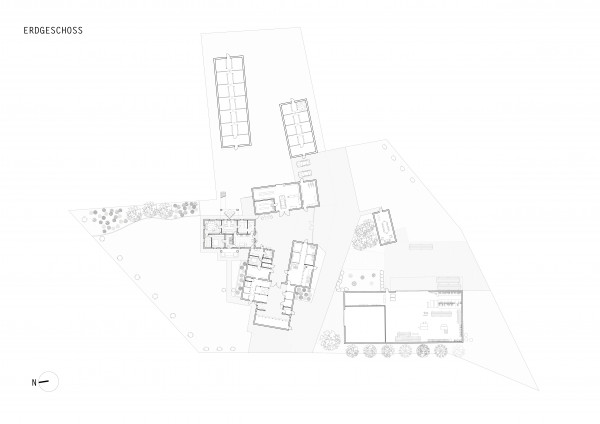

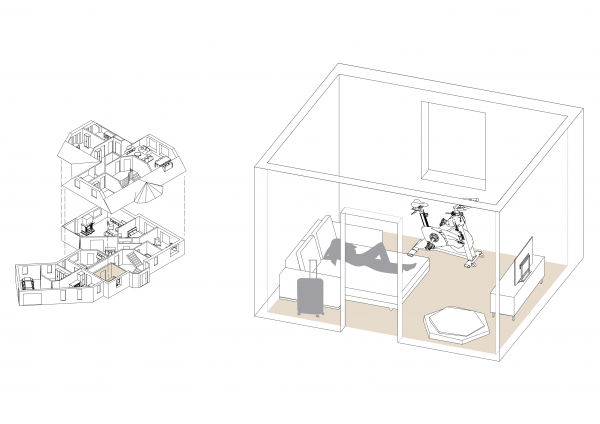

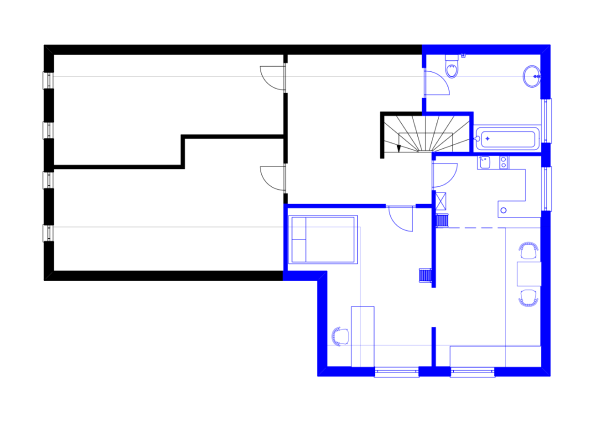

When we refer to drawing in Urban Types, we are mainly concerned with the documentation and mapping of the (everyday) use and of traces of appropriation that residents, planners and others leave and have left in and around the flats and houses in the past, and their process of becoming. We borrow from the classic instruments of the planning disciplines and create drawings of houses that show the ground floor, view, section, axonometry and isometry as diagrammes, drawings by hand and in CAD (Computer Aided Design).

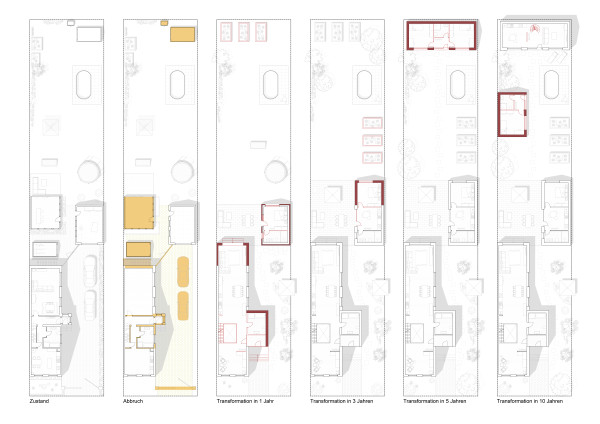

We use these instruments and tools and focus on the uses, those uses that have been taking place and those that are (still) taking place in these houses, uses by people as well as uses of things and objects of the everyday (Atelier Bow Wow 2014, 2007, 2002, 2001; Wajiro Kon 2011). “Other than in classic architectural tradition, drawing here is less conceived of as a means in order to translate an idea into a first draft, then into an operational plan and finally into a building. On the contrary, drawing is used much more comprehensively as an effective tool with which we can trace and reveal the many different realities that accompany life around architecture: habits that are reflected in architectural typologies, the influence of building techniques and building styles, the circulation of people, goods or information, the transformation of buildings and surroundings, between settlements and environment. (Kalpakci, Kajima, Stalder 2020: 3)

We attempt to capture what escapes our gaze, what at first sight is invisible; what has happened already, what happens or has happened at a different time, and we query about the possibilities of representing space not as a static entity but in an attempt to let it ‘fly’ (Latour and Yaneva 2008: 80) so as to grasp visible and invisible structures and designs (Burckhardt 2012). “Drawings here serve to understand the thickets into which architecture is embedded. At the same time, they open up new ways to proceed into the direction of an integrative architecture practice.” (Kalpakci, Kajima, Stalder 2020: 5)

Spatial appropriation, usage and planning

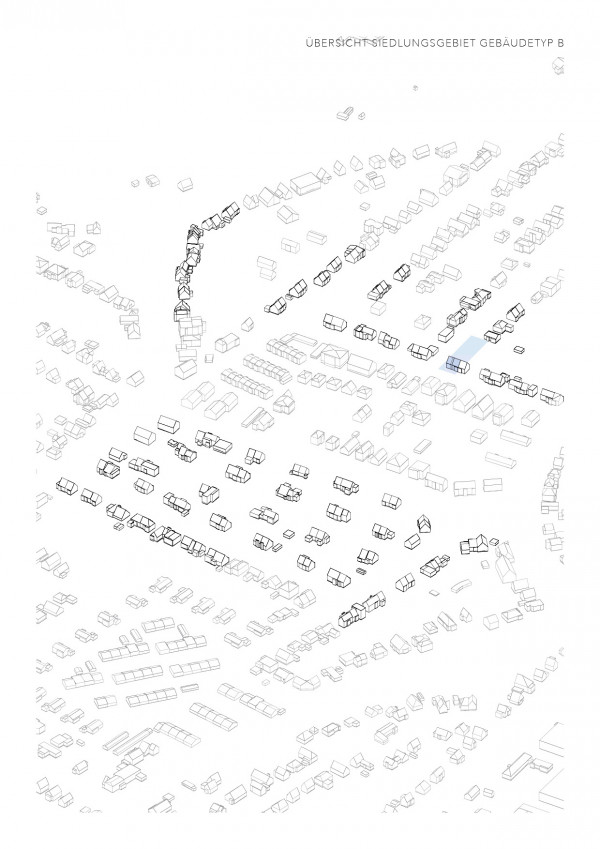

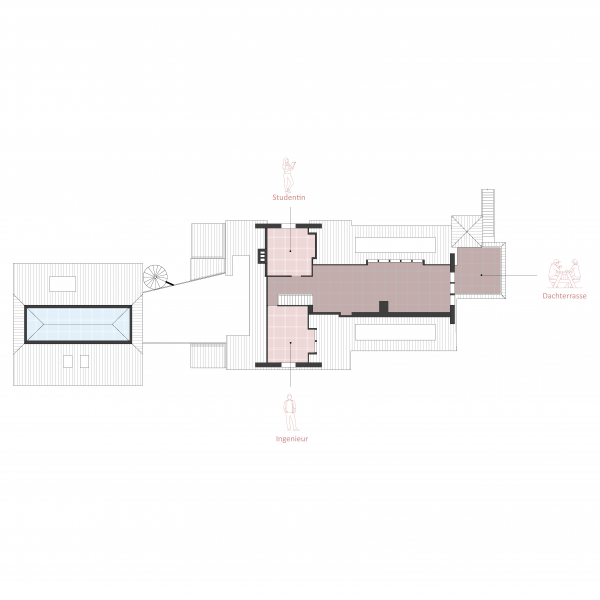

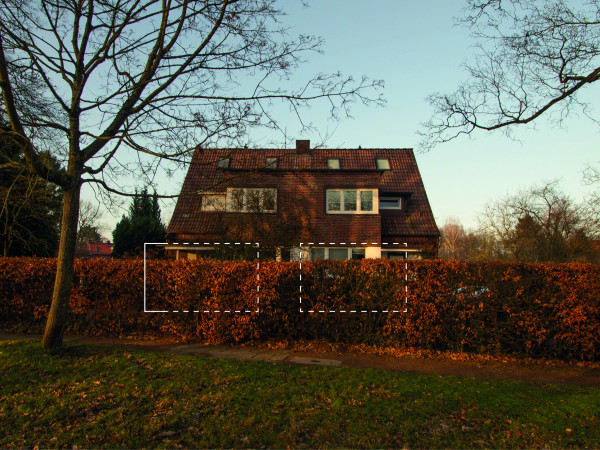

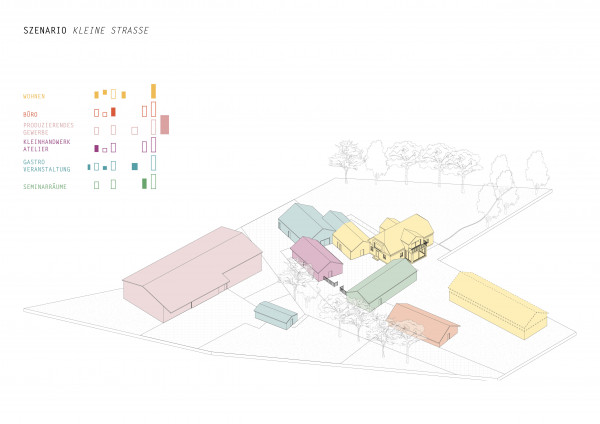

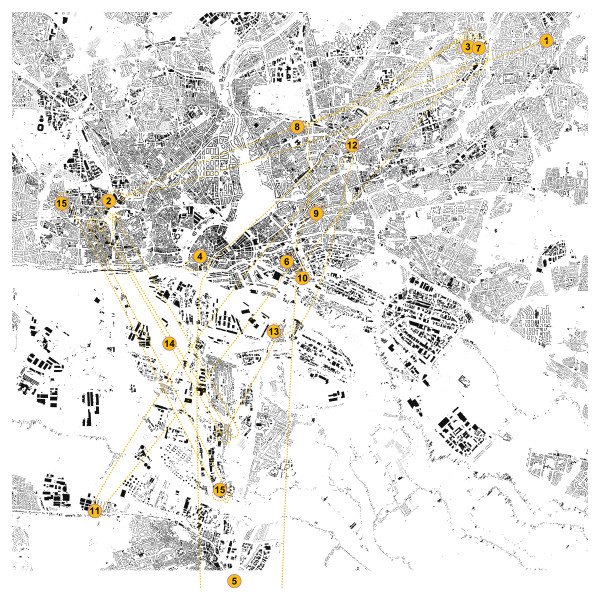

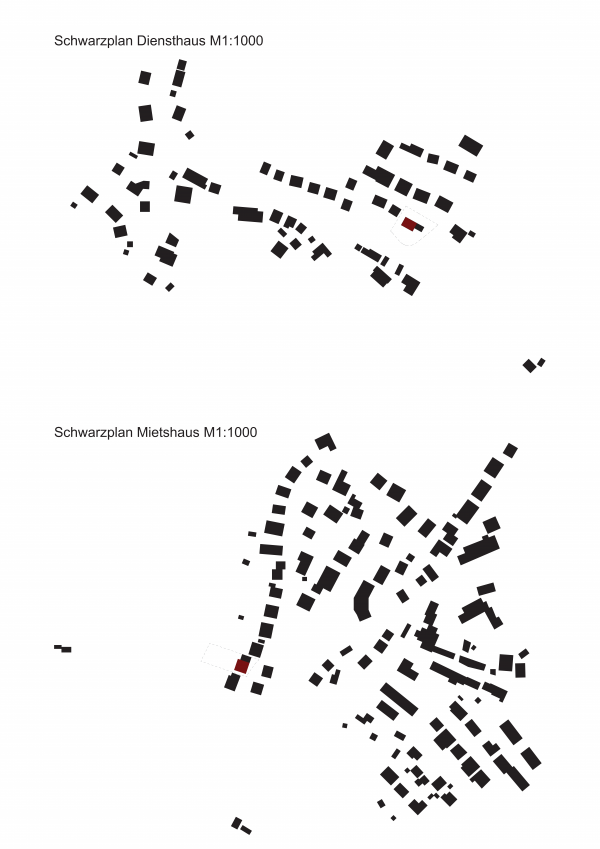

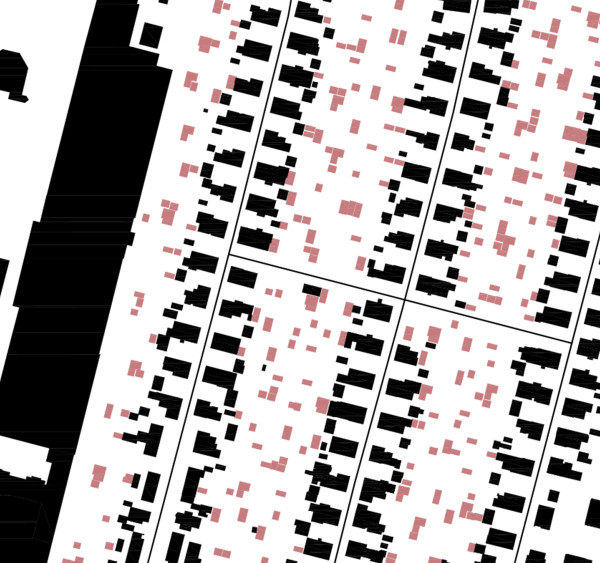

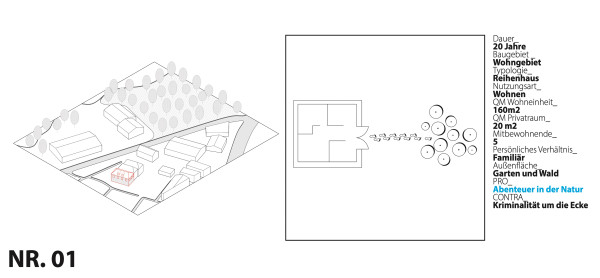

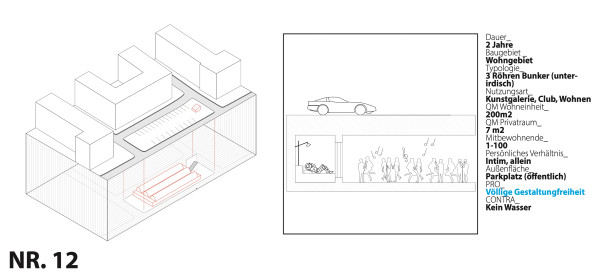

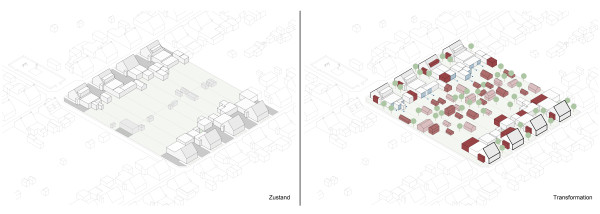

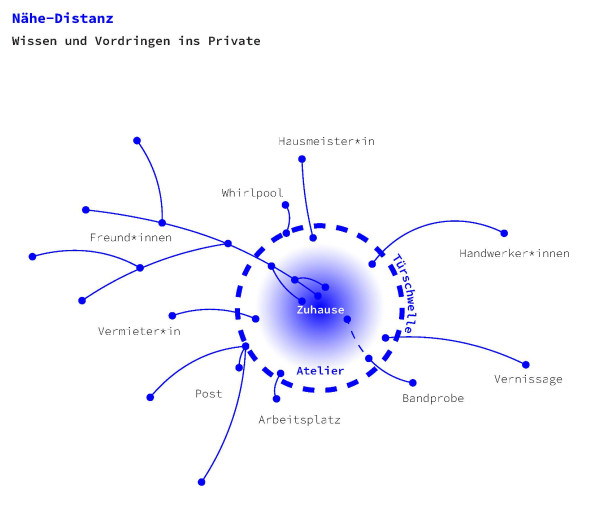

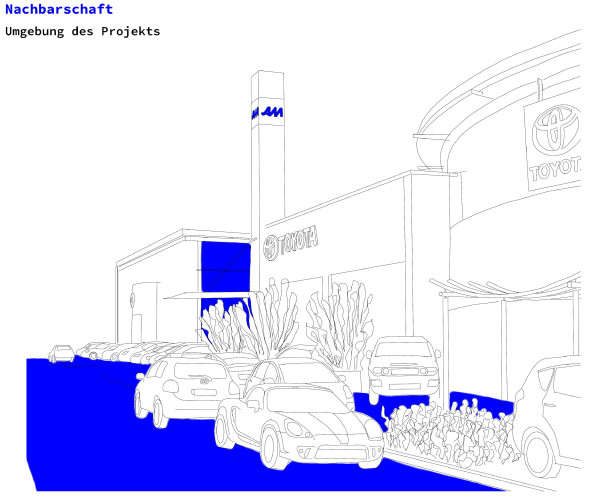

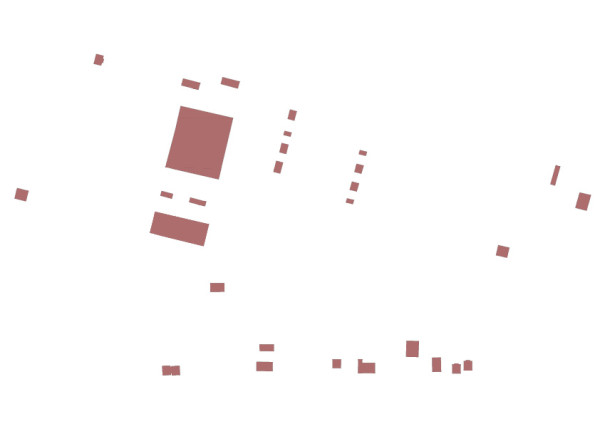

Embedded into the urban context of the immediate neighbourhood, the block parameter and the quarter as well as the city, these drawings in Urban Types are intended to show relations between social and physical as well as appropriated and planned spaces. By situating the houses in their particular typologies and according to their inhabitants, we ask for commonalities and differences, permanences and transformations (Glaser 2013), spatial functions and (dis)positions (Löw 2001), sizes and scales, materialities etc. in order to make implicit knowledges visible, verifiable and therefore open to discussion and negotiation. By drawing out, as it were, what has taken place at specific times and what exists or is performatively taking place at present can provide information regarding hidden potentials that could be further developed.

The anthropologist Tim Ingold states in an interview led by architects Momoyo Kajima, Andreas Kalpakci and Anh-Linh Ngo in an edition of Arch+ on architectural ethnography: “ Usually, art and architecture are understood as speculative disciplines, that design things that don’t exist just yet. Conversely, archeology is concerned with researching the past and anthropology with researching societies. The latter studies what is present rather than suggesting things that aren’t there as of yet. But this differentiation isn’t really coherent. You can’t speculate or design without having a deep understanding of the lived world; and a deep understanding of the lived world would be completely unnecessary if it wasn’t connected to some kind of design of how life could be. What use is it to study life, if you’re not interested in thinking about how it could be?” (Kajima, Kalpkci, Ngo 2020: 17)

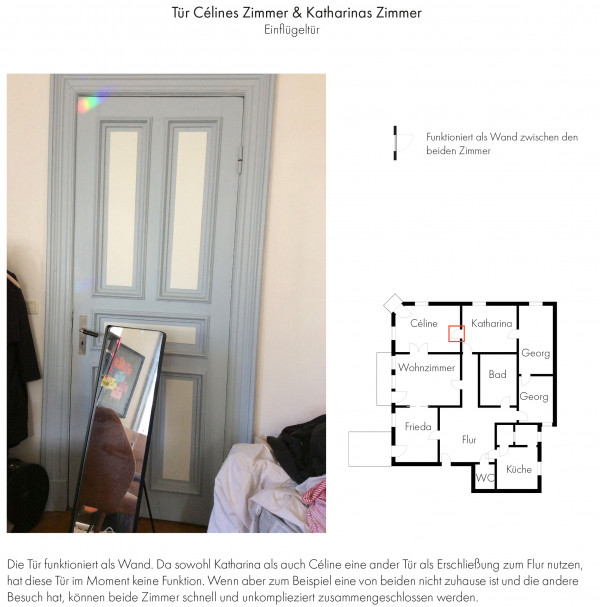

These studies that lead to said deep understanding comprise all scales of the urban and appear both in the objects (such as the door in ‘Open | closed | ajar’ and in the structure of the block (see, for instance the project ‘serially / individually’ and the different extensions of the housing types).

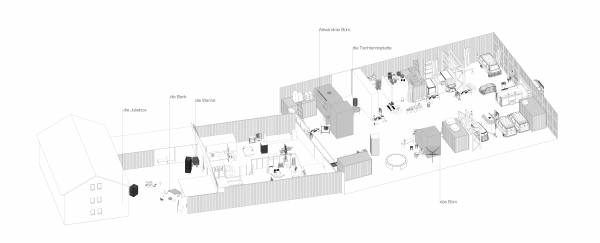

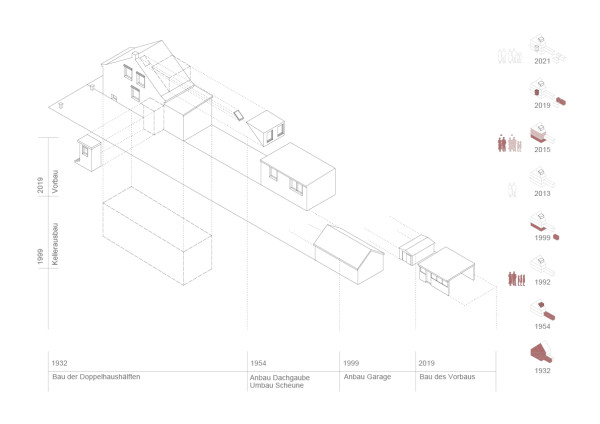

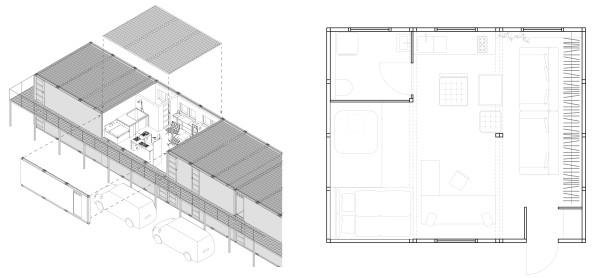

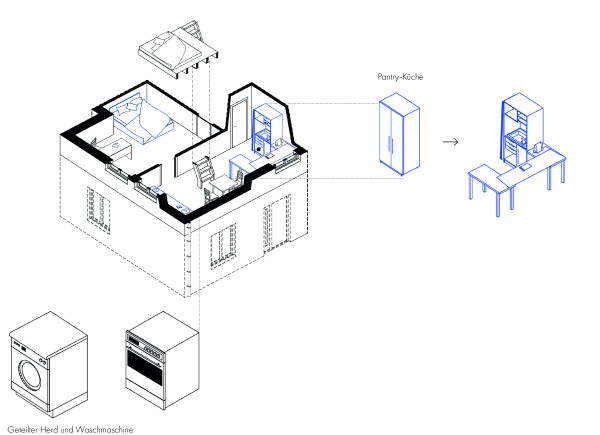

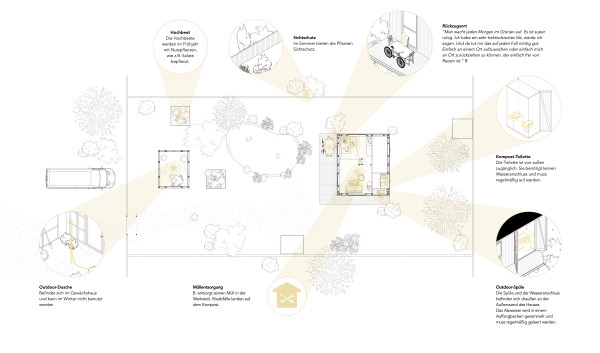

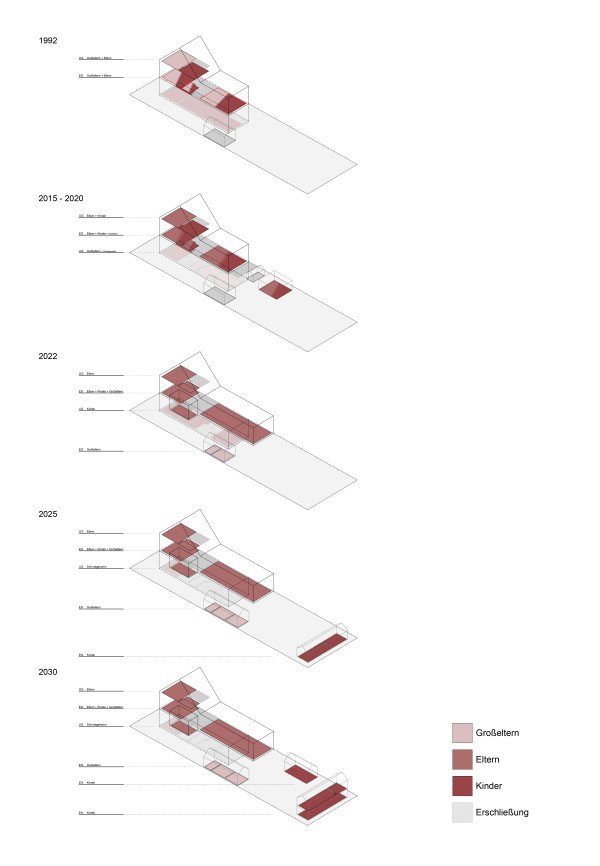

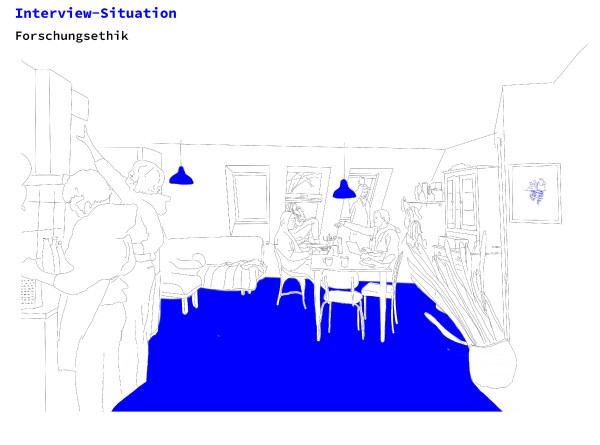

Drawing of usage implies an analysis with the people and their activities as well as their everyday objects. Spaces were, are and will be produced (Lefebvre 1974). The drawing as analysis of the existing can decipher these often already materialised or dissipated states in order to unlock potentials. Kemp (2009: 173) describes in Analysing architecture: “Building St. Peter anew has been the most grateful object in this respect; the 200 years during which the design emerged and generated is so well documented in plans, drawings and panoramas that we can gain an impression of the previous stages and the discarded alternatives [...]. Even if the analysis and research of the described object is reduced to the container space and although the design and implementation of a dome is no (longer) architecture of the everyday, much less of our concern here, what is useful for us is the presence of different planning states over a long period of time that helps to render visible the development and implementation of an existing building. Departing from a relational understanding of space, drawings can re-draw these processes in and around our studied everyday architectures that are often undocumented but orally told or related through interviews and sometimes visible in images. Thick drawings can act as as thick descriptions (Geertz 2012), where their formulation allows this (see the project ‘Living and working under one roof’).

Analysis of artefacts and traces

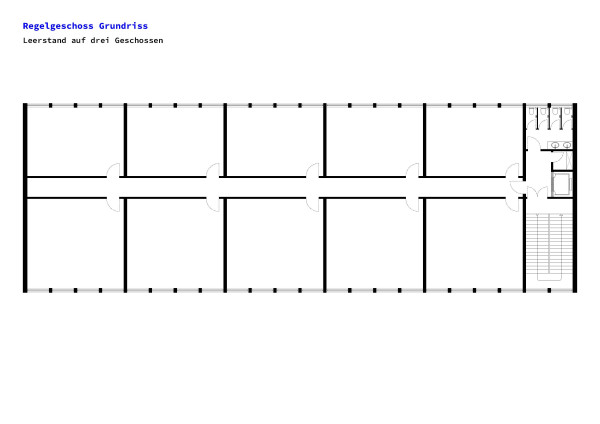

Floor plans can be represented as ‘standardised artefacts’ (Wolff in: Flick 2009: 503) in the widest sense in qualitative research and therefore subsumed under the analysis of documents and files. It is particularly interesting that Flick states that most of the official and private documents ‘are only meant to be read by a specific circle of legitimate and addressed recipients’ (Wolff in: Flick 2009: 503). Yet these documents can also count as ‘institutionalised traces’ and by way of analysing these offer conclusions about their authors and, moreover, their organisation(s), social relations, conditions, situations etc. We find such references and relations between built matter and social structures in Norbert Elias’s studies on the courtly society, where he intends to represent these interplays and their expression in built structures (using, for instance, the French manor). We find similar examples, if concentrated on the transformations over the course of history, in Robin Evans’ essay Figures, Doors and Passages as well as in studies focusing on existing power relations (see Dörhöfer 1998; Heynen 2005; Nierhaus 1999).

Connected to our motifs in Urban Types we are concerned with laying open and making accessible this knowledge that is inherent in the material (both in terms of form and activity), in our case: the inhabiting of houses. Drawing can be a possible instrument or a possible expression in researching, exploring, studying and making accessible and visible these inventories of knowledge (or to keep them deliberately concealed).

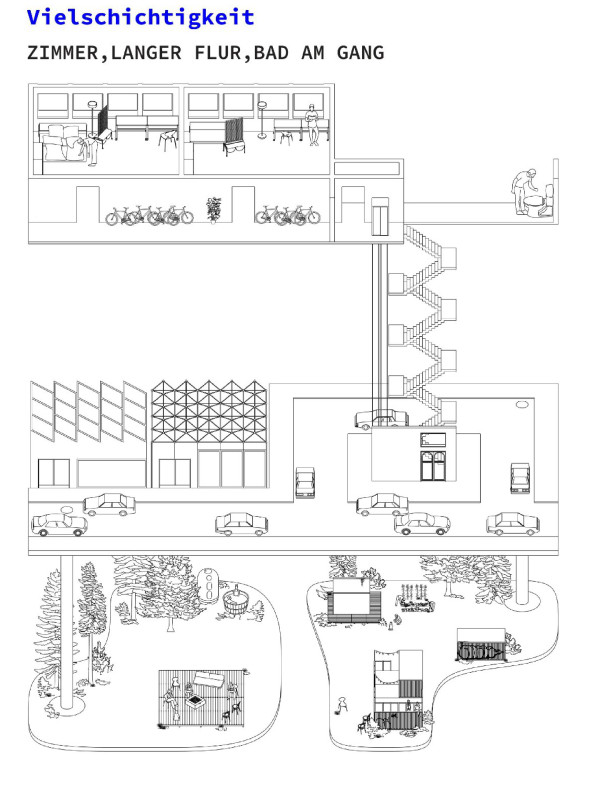

Vertiefung

1. Akt: Prolog - Wohnen und Arbeiten auf Theaterbühnen

Zug um Zug 2 – die Wanne

Versorgungsmöglichkeiten

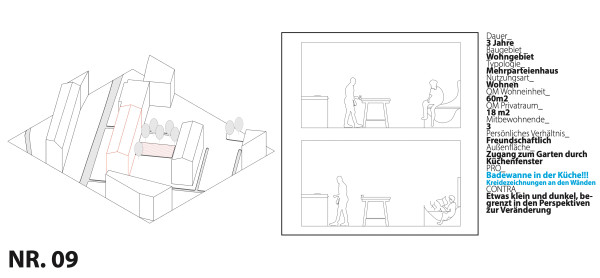

Isometrie mit Interview- ausschnitten

Familiengeschichten - Szenario: Obst- und Gemüseanbau

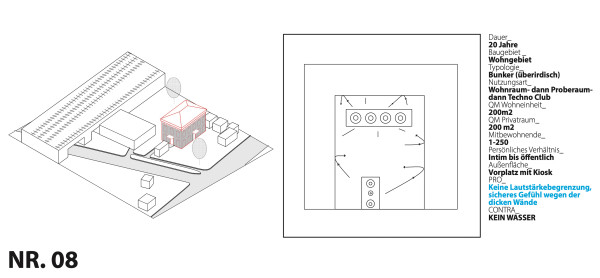

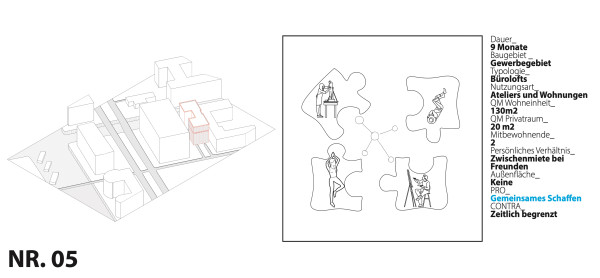

Modellprojekte Steckbriefe

Entwicklung Zeitstrahl

Zug um Zug 2 – die Jukebox

Zug um Zug 2 – das Büro

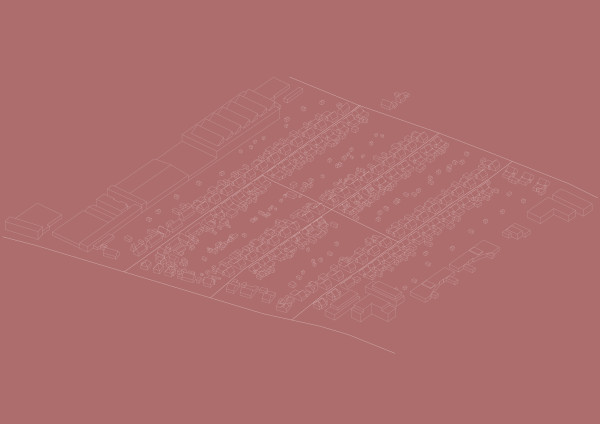

Zeitstrahl der Flächennutzung

Wachstum, Gemeinschaft

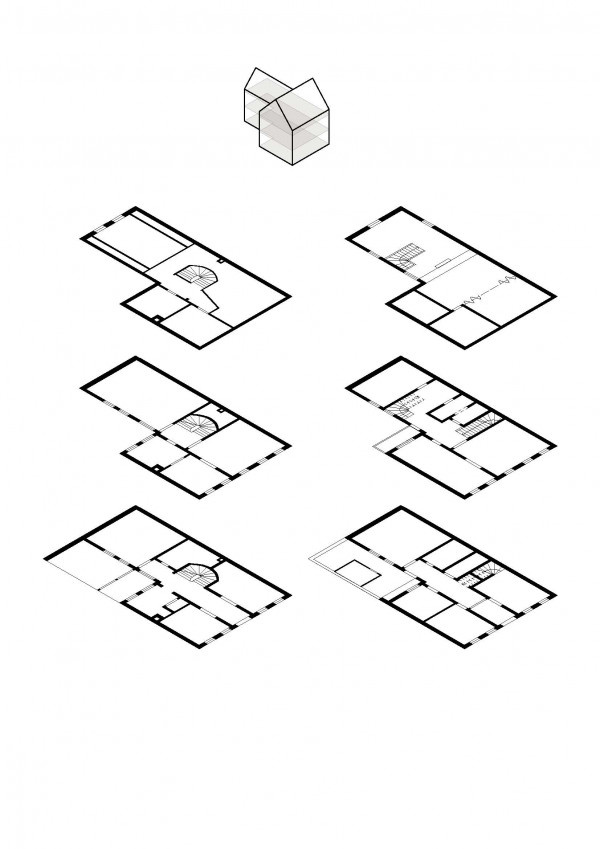

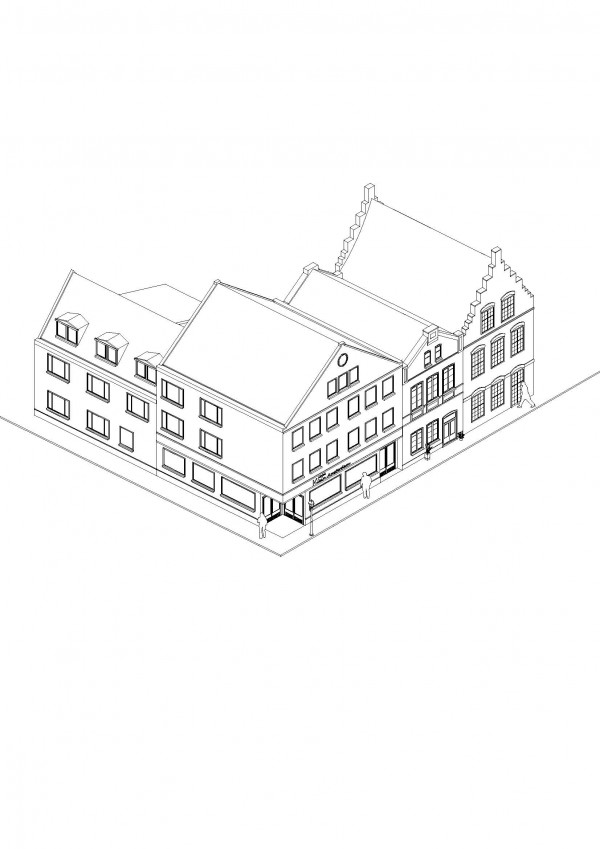

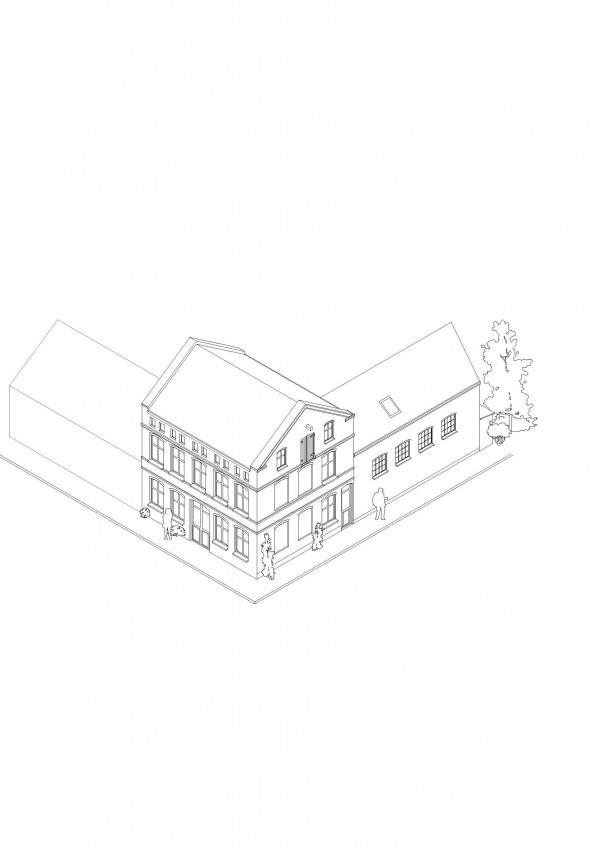

Historische Entwicklung der Bauvolumen

Gruppenraum

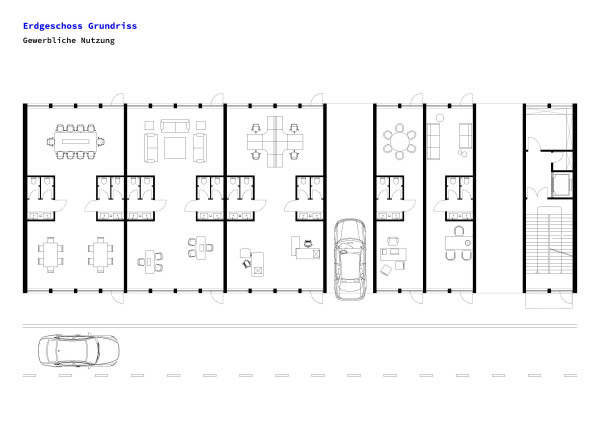

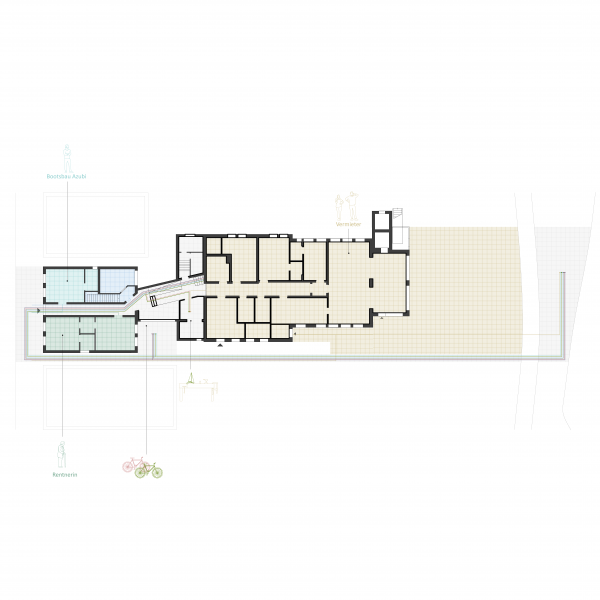

Grundriss

Interview

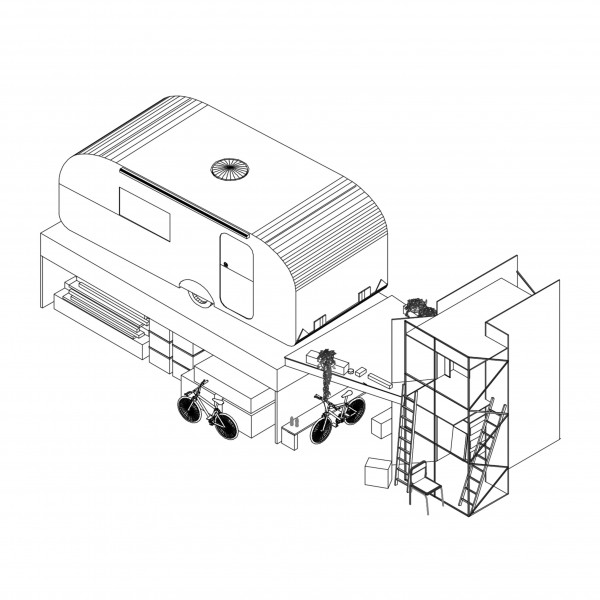

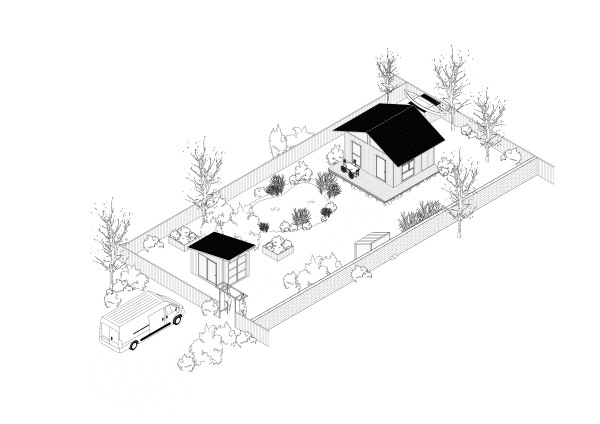

Zug um Zug – Isometrie außen

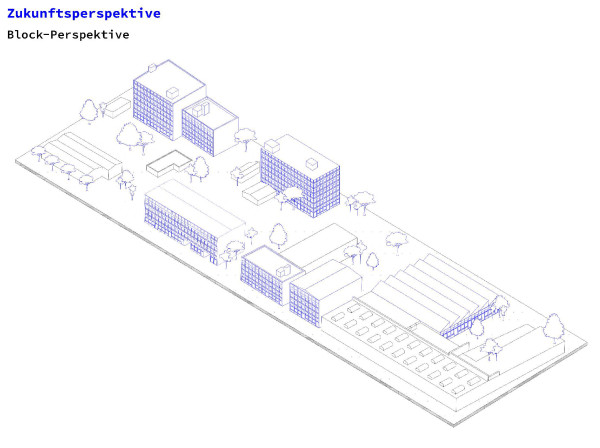

Schwarzplan — zukünftig

Familiengeschichten - Szenario: Gartenlaube und Terrasse

"ungeschriebene Gesetze"

Die drei Wohnungen sind generell separat voneinander zu betrachten. Es gibt einen gemeinsamen Hausflur und das Treppenhaus nebst Aufzug, welches die drei gleich großen und nahezu identisch gestalteten Wohnungen miteinander verbindet. Die Wohnungen und den Flur trennen jeweils auch drei Wohnungseingangstüren, sodass das Wohnen im gesamten Haus generell nicht als gemeinschaftlich…

Continue reading...

Zug um Zug 2 – die Tischtennisplatte

Familiengeschichten - Szenario: Wohnen im Garten

2. Akt: Darsteller:innen und Requisiten

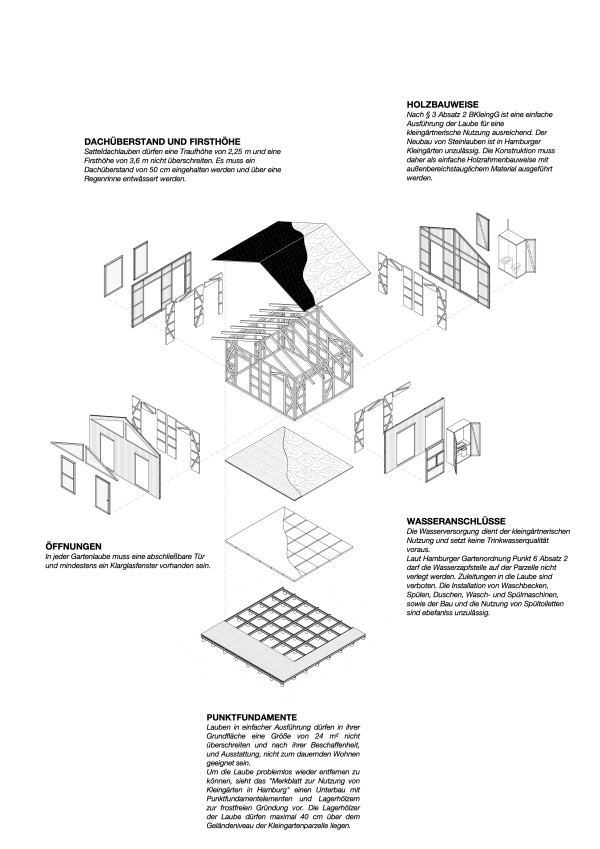

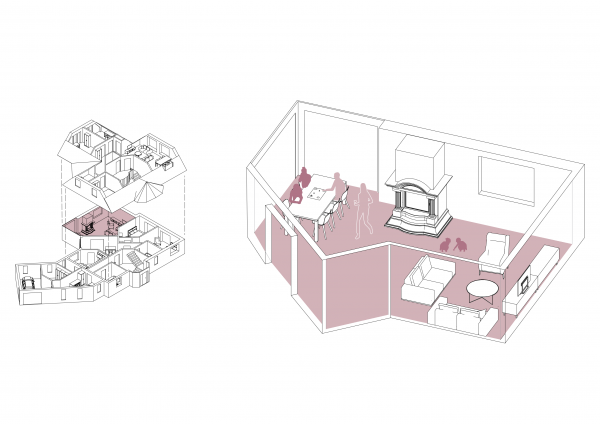

Explosionsisometrie mit Interviewzitaten

Zug um Zug 2 – die Bank

Das Frauenstift im zeitlichen Verlauf

Familiengeschichten - Katalog Wohnqualitäten

Familiengeschichten - Grundrisse der Zukunftsvision

Familiengeschichten - Grundrisse heute mit Interviewzitaten

5. Akt: Blick in die Vergangenheit...für den Wurf in die Zukunft!

Familiengeschichten - Zeitstrahl

Familiengeschichten - Szenario: Scheune

Zug um Zug – Isometrie innen

1932-2021